Published by South China Morning Post, images from South China Morning Post.

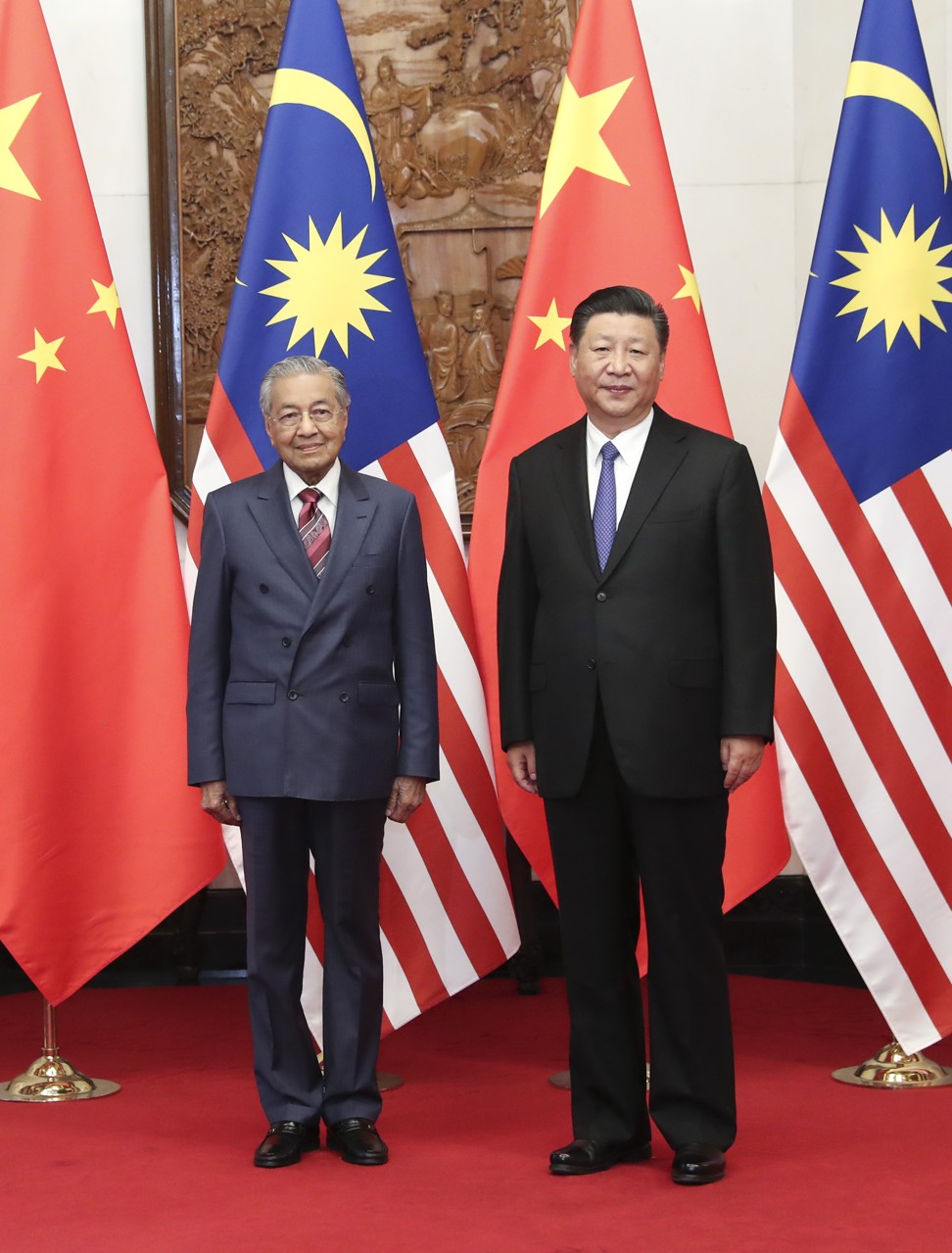

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad will this week attend the second Belt and Road Forum in Beijing to discuss bilateral ties. This will be his second official visit to China during his current term as prime minister and his ninth visit overall.Unlike his last visit to China in August 2018, this time he returns as a committed supporter of the “Belt and Road Initiative”. He was among the first to confirm his attendance in February and by mid-April, Putrajaya and Beijing announced new terms for the East-Coast Rail Link (ECRL), one of the project’s key links.

The cost has been cut by more than one-third to about US$10.68 billion from the previous US$16 billion, with about US$5.3 billion paid in advance. Malaysia will contribute more raw materials and labour – up to 70 per cent, with the remaining 30 per cent coming from China and other Asian countries.

Malaysia has therefore become a successful case study for the ongoing implementation of belt and road projects. It no doubt helped that Mahathir was able to present his concerns in the most non-confrontational manner possible, emphasising domestic concerns rather than any particular anti-Beijing sentiment.

In its election manifesto, Mahathir’s Pakatan Harapan coalition promised to revise Malaysia-China megaprojects in its first 100 days of power. Mahathir insisted Malaysians should benefit from foreign investment and, on his visit to China in August 2018 after becoming prime minister, he warned of “new colonialism” and “debt trap diplomacy”.

When Mahathir visited the Philippines in March, he urged President Rodrigo Duterte to avoid such debt traps and also warned of a “foreign influx”, referring to some 200,000 Chinese working in the country.

However, Mahathir told the South China Morning Post Malaysia preferred China’s stability to the unpredictability of the US. He indicated this consideration was “purely economical” and stressed Malaysia saw little threat in China’s growing regional influence – or in Huawei’s expansion of 5G technology, for example.

These policies suggest a balancing act: catering to the electorate at home, maintaining sovereignty and assessing the viability of a bold stance towards international partners such as Beijing.

Some observers suggest Malaysia has plenty of room to move. In reality, it finds itself in a tight spot with limited options.

Pakatan Harapan has been struggling to fulfil its campaign promises, particularly when it comes to undoing the work of the previous government. The original agreement for the ECRL apparently did not include a proper exit clause and Malaysia would have been compelled to forfeit the US$5.3 billion paid upfront if it cancelled the project. Taking into account the projections the ECRL will lose money anyway, there was no perfect solution.

Nevertheless, the ECRL fits neatly into Mahathir’s geopolitical vision and his non-aligned narrative. Malaysia is not in a position to suggest any grand project of a global scale on its own, preferring cooperation with China, its largest trading partner.

Even though Malaysia does not qualify as a traditional “middle power”, it has sought to cast itself and conduct itself as an emerging one.

In its relationship with China, Malaysia has emphasised its non-aligned status, while also seeking to maintain regional order and remain open to compromises. On the issue of China’s treatment of its Muslim-minority Uygur population, Malaysian expressed concerns privately but apparently left it to Turkey to openly criticise Beijing’s policies.

Malaysia’s stance is a strategic consideration stemming from pressure placed on its palm oil exports by the impending European ban. As a result, Malaysia has become increasingly interested in dealing with China, agreeing the sale of 1.62 million tonnes of palm oil worth US$891 million.

“This is going to be a great relief for the palm oil industry,” Primary Industries Minister Teresa Kok said in March.

With the settlement of ECRL and reopening of the Bandar Malaysia project between Malaysia and China, there has been assurance of even larger palm oil purchases coming from Beijing. Mahathir is therefore not only the leader of a middle power government but a middle man reconciling his country’s interests abroad with public opinion at home.

In a 2014 study by Pew Research, Malaysians identified China as its greatest ally and the US as one of its biggest threats. Nonetheless, any overzealous attempts to forge closer ties with China would likely provoke backlash, in light of ethnic divisions and suspicions over the allegiances of Malaysian Chinese.

This balancing act will therefore require diplomatic tact and sophistication, both from Mahathir and Anwar Ibrahim, his designated successor, and communicating these broader strategic objectives to voters at home will be a challenge in its own right for Mahathir upon his return from Beijing.

Julia Roknifard is Director of Foreign Policy at EMIR Research, an independent think-tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based upon rigorous research.