Published by TheStar, image by AstroAwani.

Malaysia’s innovation story has long been told in the language of aspiration, the familiar refrain that the country stands on the cusp of becoming a knowledge-driven economy. However, real progress begins with truth, and the truth is that Malaysia’s innovation journey has reached a point of uncomfortable clarity, revealing structural weaknesses that can no longer be ignored. The Global Innovation Index (GII) for 2024 and 2025, as well as the deeper indicators beneath it, make this point unmistakably.

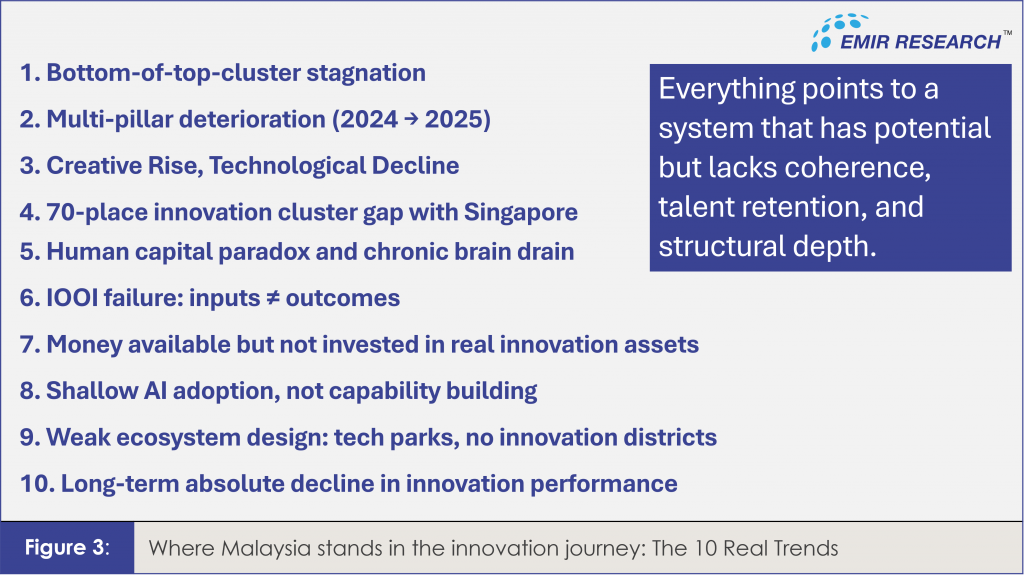

Across both 2024 and 2025, Malaysia stays at the very bottom of the top-country cluster (GII Heatmap 2024, 2025). This stable position may sound comforting to some, but a stagnant position inside an otherwise extremely dynamic group is not evidence of resilience. It is evidence of inertia. This becomes even clearer when we examine the structural pillars that form the foundation of an innovation economy.

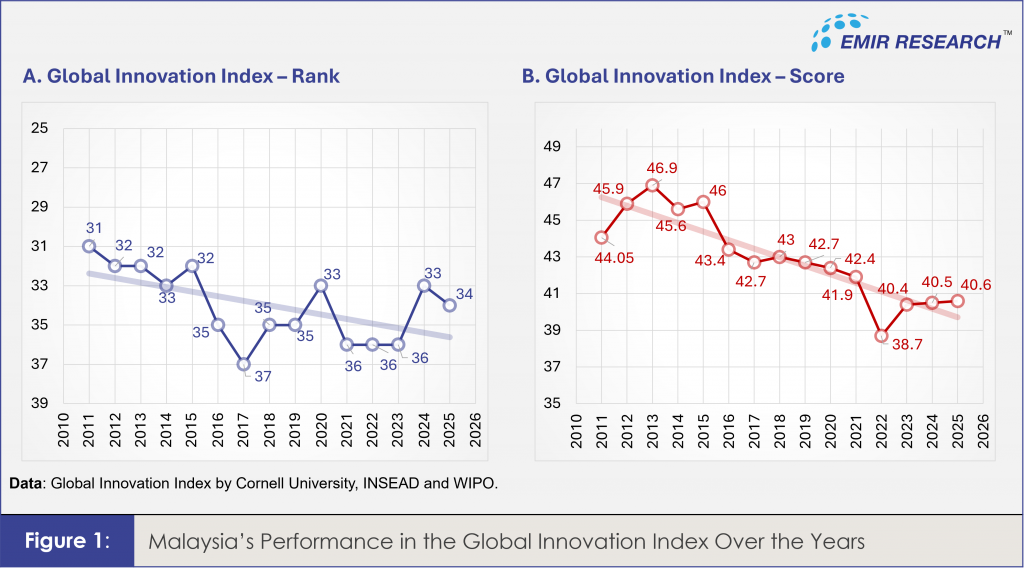

Before examining the pillars themselves, it is worth observing how this structural erosion has accumulated over time—a decline captured starkly in the decade-long downward slope of Malaysia’s GII score, even as its rank meanders without real upward momentum (Figure 1).

Human Capital and Research—arguably the most essential pillar for any nation hoping to compete in the age of AI and deep technology—fell sharply from 38th to 46th place. Infrastructure slipped further from 52nd to 54th, Institutions weakened from 27th to 30th, and Business Sophistication declined from 36th to 38th. These are not random pillars but backbone that constitute the essence of a nation’s innovation readiness with profound implications for the years ahead.

In recent years, the only consistent improvement in the GII has come not from knowledge creation, scientific advances, or commercialisation of technology, but from Creative Outputs—driven primarily by entertainment, media, digital content and brand value. This upward trajectory in creative sectors is encouraging in its own right as it reflects cultural vitality, digital participation, and the emergence of a generation adept at shaping narratives and producing content. But it also masks a more troubling reality: the pillars that define a technologically advanced, innovation-led economy are deteriorating at the same time.

Knowledge creation has weakened across nearly every relevant metric. Patents by origin are stagnant or in decline. Patent Cooperation Treaty patents—the clearest indicator of globally competitive innovation—have worsened sharply. Utility models show no progress. Even the volume and quality of scientific and technical articles have dropped, with Malaysia slipping from 51st to 69th place in a short period.

Knowledge impact follows the same pattern. Labour productivity, perhaps the most fundamental measure of an economy’s technological absorption, has worsened significantly. Unicorn activity remains negligible. Software spending is not rising meaningfully. And the country has not developed the domestic technological champions needed to translate ideas into high-value enterprises.

Knowledge diffusion, meanwhile, has flattened. Production and export complexity has fallen. ICT services exports remain weak. ISO 9001 quality certifications have declined. Intellectual property receipts, which signal the export of knowledge-intensive goods and ideas, remain stagnant.

Taken together, these indicators suggest that Malaysia is steadily improving as a producer of content but steadily weakening as a producer of technology. This dual-speed innovation profile where one part rising, the other part falling signals imbalance rather than genuine innovation strength. Creativity is a strength, but without strong technological foundations it risks becoming ornamental rather than transformative.

This imbalance is further reinforced by the stark contrast between Malaysia’s innovation clusters and those of its neighbours. Kuala Lumpur appears for the first time in the global list of top 100 clusters, ranked 93rd in 2024 and 86th in 2025. This should be a milestone worth celebrating. Yet the cluster Malaysia shares with Singapore ranks 16th—a gulf of seventy places across a narrow geographical divide. This disparity cannot be attributed to culture, demographics, or natural resources. It is a systems problem: density, talent concentration, institutional quality, and the ability to convert ideas into real economic value.

The contradictions extend into human capital as well. Malaysia continues to rank first globally in the share of science and engineering graduates yet simultaneously ranks 48th in PISA scores and 77th in tertiary enrolment. Industry participation by knowledge workers remains low. Employer surveys consistently highlight gaps in technical competence despite high credential numbers. And above all, Malaysia continues to face what EMIR Research has repeatedly described as its most persistent structural wound: the steady outflow of its brightest talent. When high graduate output is accompanied by low competency, weak industry absorption, and sustained brain drain, the human capital pillar will continue to erode no matter how many graduates the system produces.

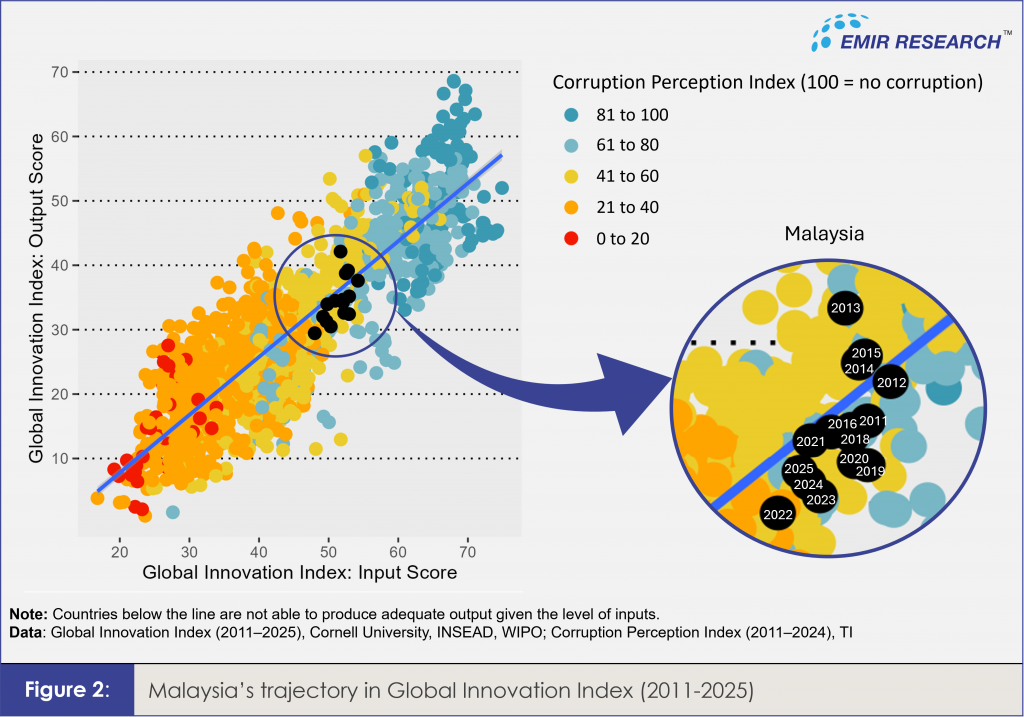

This leads naturally to the broader issue of misalignment between inputs, outputs and impacts. For more than a decade, Malaysia’s absolute GII score has experienced what analysts describe as a “steady and steep decline.” Inputs are not only not rising meaningfully but do not translate into optimal outputs (Figure 2). As result, outcomes and impacts remain persistently weak.

Malaysia’s R&D spending has hovered around half a percent of GDP which is far below innovation leaders. But even more concerning is the way these funds are deployed. The system continues to produce pilot projects, isolated initiatives, and fragmented programmes that rarely reach commercialisation. Apparently, Malaysia does not suffer from a shortage of innovation initiatives; it suffers from a shortage of innovation that translates into value.

One might expect a mature financial system to compensate for these weaknesses, yet the Market Sophistication pillar reveals another paradox. Malaysia ranks second globally for credit availability, with a score nearing 94, yet ranks 86th in gross capital formation. Capital exists, but it is not channelled into productive assets. Funds circulate within the system, but the investments that build long-term innovation capacity—research facilities, design centres, labs, advanced manufacturing—remain underdeveloped. The gap between liquidity and productive investment is widening.

Meanwhile, Malaysia’s adoption of advanced technology remains shallow. According to the latest AWS and Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers reports, 27 percent of firms report using AI, but only a fraction use it to build new products. Most applications are basic, automating surface-level tasks rather than enabling new capabilities. Manufacturers show similarly low adoption rates. The pattern mirrors Malaysia’s broader innovation challenge: the system uses technology but does not yet create it.

Beyond the numbers, the physical and institutional architecture of Malaysia’s innovation ecosystem has not kept pace with global trends. Technology parks remain isolated, single-use developments that struggle to facilitate the dense, serendipitous interactions that define real innovation districts. Knowledge flows depend on formal channels rather than organic spillovers. Collaboration remains structured rather than spontaneous. This design, inherited from an earlier economic era, cannot generate the energy, culture or density required to sustain technological breakthroughs.

All of these trends summarised in Figure 3 reflect the same underlying truth: Malaysia’s innovation system has potential, but it lacks coherence and depth. The nation stands at a point where incremental adjustments will no longer suffice.

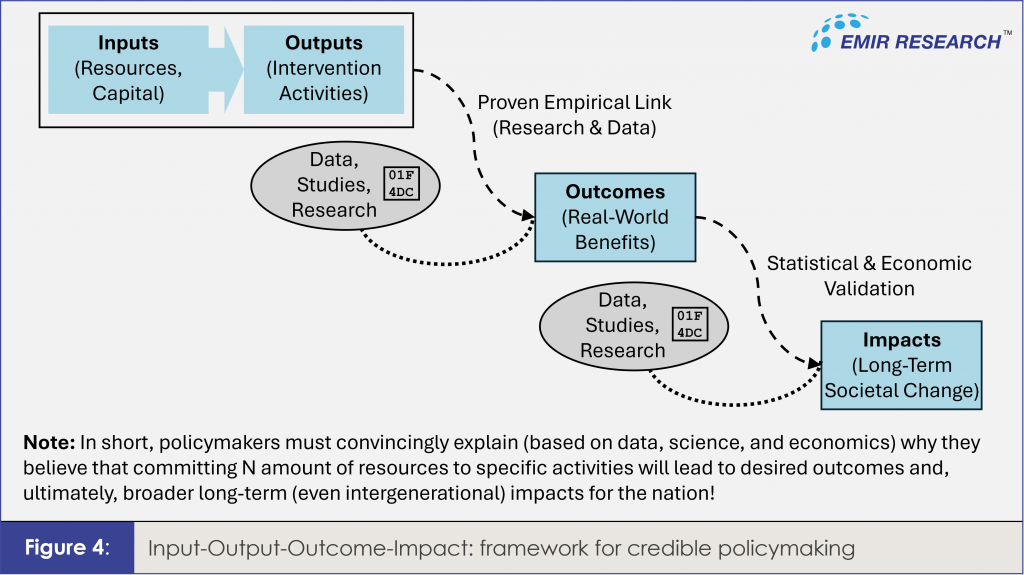

To succeed in an era defined by AI, quantum technologies, and sovereign data ecosystems, Malaysia needs structural alignment—between talent and institutions, between governance and outcomes, and between ambition and execution. It needs to move beyond programme-based approaches toward systems-based reforms grounded in the IOOI logic that translates inputs into real-world impacts (Figure 4). It needs to retain its brightest minds, empower researchers, redesign its innovation spaces, rebuild its educational foundations, and invest not merely in tools but in capabilities.

Malaysia is not starting from zero. The country has ambitions worth defending, ecosystems worth strengthening, and young talent worth believing in. But to turn potential into progress, the system must focus not on the volume of activity but on the quality of outcomes. A high-income, innovation-driven future will not emerge from the number of programmes launched or the number of graduates produced. It will emerge from the discipline to measure what matters, to build what lasts, and to align national effort with national impact. Only then will Malaysia not merely adapt to the future but help shape it.

Dr Rais Hussin is the President / CEO of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.