Published by The Star, MySinchew, NST (print) and NST (online); image by NST (online)

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s warning on the perils of artificial intelligence (AI) spending captures Malaysia’s dilemma: spend without discipline and billions will be wasted, hesitate too long and the nation risks being left behind in the next wave of technological sovereignty. Whatever AI may be, Malaysia must strike a balance: rigorous safeguards against waste and corruption, alongside bold investment to ensure the nation is not left behind in quantum-AI convergence, chip design and sovereign data ecosystems.

He is right that billions risk being wasted if AI becomes a fig leaf for inefficiency or, worse, corruption. AI comes with a massive hype bubble, and Malaysia, like many countries, risks burning billions without returns if projects are launched without strategy, oversight and clear metrics.

The “AI productivity paradox” the Prime Minister cited is real. Studies show that chatbots and automation can save users 64 to 90 per cent of time, yet only a fraction of these gains translate into higher earnings or productivity. History is littered with such disappointments: the much-heralded “paperless office” of the 1980s ended up increasing paper use instead of reducing it.

However, the paradox is not only about numbers.

As MIT’s system design framework reminds us, effective organizations thrive on the “four Ss”: simplification, standardization, stabilization and synchronization, and AI is a natural fit to excel on all four. One of the framework’s counterintuitive lessons is that high-performing systems deliberately leave slack: no worker is fully loaded, so that unforeseen delays can be absorbed and, crucially, new ideas can be tested. Slack, however, is like oxygen — it can fuel innovation, or it can leak into waste. AI promises to generate slack by saving time, but unless the people using it have capability, accountability, and a culture of experimentation, those gains risk vanishing into idleness.

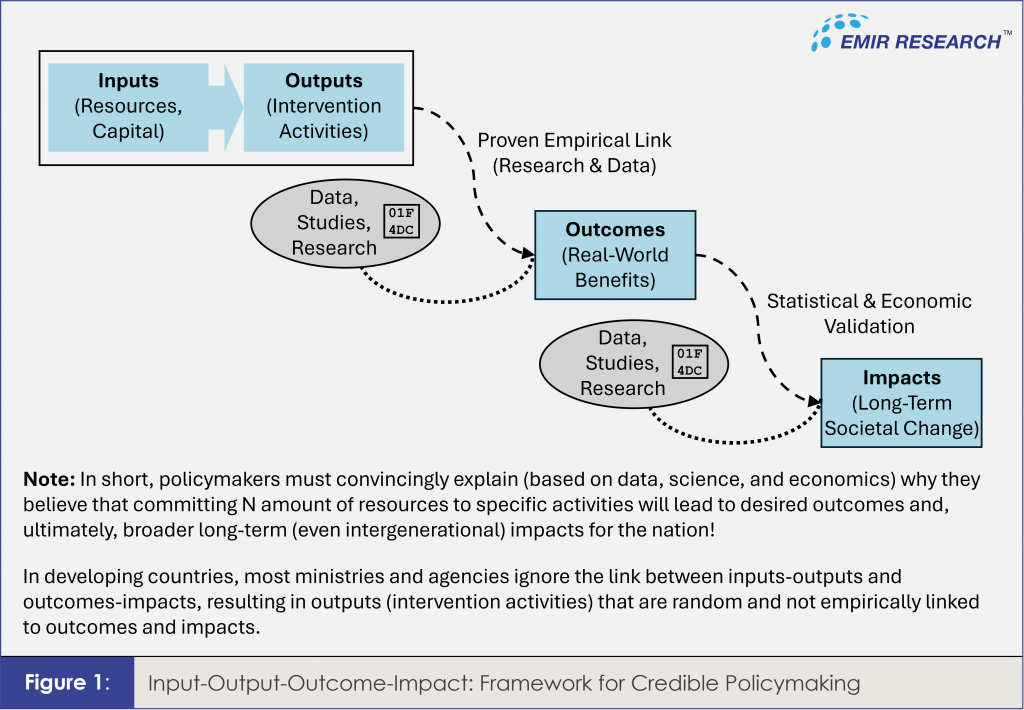

AI’s potential ultimately depends on the intelligence of the people and institutions using it. Even if governance is tightened, Malaysia will not reap AI’s potential without addressing three deep structural gaps. First, institutionalizing the Input–Output–Outcome–Impact (IOOI) model across ministries and agencies, so that every ringgit is tracked not just in inputs and outputs but in real outcomes and impacts. Second, tackling the brain drain crisis with credible reforms: our brightest talent continues to leave because of low prospects, weak institutions, and poor recognition, as EMIR Research has documented through decades of empirical studies. Third, overhauling education so that schools and universities produce critical thinkers and innovators rather than paper credentials. Unless these are addressed together, Malaysia will fail to capture AI’s full potential.

Institutionalizing the Input–Output–Outcome–Impact (IOOI) framework across government is critical. As EMIR Research argued in “Transforming Malaysia from third- to first-world country” and “Recalibrating National Budget – Eradicating Leakages and Corruption”, IOOI provides the logic chain that ensures resources translate into real outcomes and impacts, while curbing leakages and embedding accountability (Figure 1).

But accountability frameworks alone are not enough. Even the best-designed systems collapse without the talent to drive them. The brain drain is Malaysia’s most persistent structural wound. Decades of research show that our brightest leave not simply for higher salaries, but because of systemic issues: limited career pathways, weak institutions, and poor recognition of merit. EMIR Research’s “Malaysian Brain Drain: Voices Echoing Through Research” highlights how this exodus erodes innovation capacity, undermines sovereignty, and effectively subsidizes other economies. Without serious reforms to retain and reward talent, AI investments will continue leaking out through human capital flight.

And even if Malaysia retains its brightest minds, they must be nurtured by an education system that equips them to innovate rather than conform. Yet Malaysia has lost at least a decade compared to leading systems, with declining STEM uptake, under-qualified teachers, and an over-reliance on rote learning. EMIR Research’s “Urgent Need to Reform Malaysian Education System” underscores that only through deep reforms—early STEM exposure, high teacher standards, equity across rural and urban schools, and curricula fostering critical and creative thinking—can Malaysia create a workforce ready to innovate with AI rather than merely consume it.

These three gaps are deeply interlinked. Institutionalizing IOOI would align ministries around real outcomes, reducing frustration and restoring trust—key factors in retaining talent. Solving brain drain would in turn ensure that investments in education are not a subsidy to foreign economies, but a foundation for Malaysia’s own AI-driven future. And an education system that produces innovators rather than paper credentials would strengthen both governance capacity and talent retention. Together, these reforms create a virtuous cycle, ensuring that AI becomes a catalyst for transformation rather than a costly illusion.

So, caution, on its own, is not a policy. Warning against “AI as a cover for inefficiency or corruption” is critical, but unless paired with a concrete national AI governance framework—covering procurement standards, evaluation metrics, and independent oversight—it risks becoming rhetoric. Countries that succeed with AI (say Singapore or South Korea) don’t just caution against failure; they embed AI adoption in strict governance ecosystems, while also fostering research, talent, and experimentation. Otherwise, Malaysia could fall into the opposite trap: risk-aversion that slows adoption just as global competitors accelerate.

This is not only a regional race. The United States, China and the European Union are already competing to set the standards, infrastructure and governance models of AI. If Malaysia lags, it risks being locked into dependence on foreign platforms and algorithms, with little say over how its data or sovereignty are managed.

Malaysia too must move beyond warnings to build its own AI governance framework—anchoring transparency, performance measurement and ethical use. But governance alone is not enough: it must also catalyze innovation by investing in sovereign data ecosystems, semiconductor design, and the coming convergence of AI with quantum technologies. If governance is the brake, then innovation is the engine—both are needed to drive the economy forward.

Invoking the principle of tabayyun—verification—Anwar is right that AI is not absolute and must never replace human judgment, especially in sensitive domains. Yet verification must be matched with vision. Otherwise, Malaysia risks repeating a familiar mistake: spending not on wasted systems, but on wasted opportunities.

The real danger is not just wasting money on failed AI projects, but wasting the chance to transform Malaysia’s future. Anwar is right that caution is needed — yet as the opening warning reminds us, it is double-edged. Without the matching edge of strategy, caution itself becomes Malaysia’s gravest mistake.

Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.