Published by BusinessToday, DagangNews, NSTOnline, MySinchew and TheSun, image by BusinessToday.

Budget 2026 will be one of the most closely watched in recent years. It comes at a moment when Malaysia must reconcile two competing imperatives: fiscal discipline and social protection. The government faces the hard arithmetic of slowing global growth, elevated debt, and a subsidy system under strain — yet it must also preserve the moral centre of the Madani agenda, which is to protect households from falling behind.

Public debt is already near the self-imposed ceiling, while global headwinds — from China’s slowdown to volatile capital flows and rising climate costs — make the policy space even tighter. Any move that resembles austerity could trigger political backlash. Yet doing nothing risks credibility with investors and credit agencies. The fiscal story, therefore, cannot just be one of restraint; it must also be one of renewal.

Subsidy rationalisation sits at the heart of this balancing act. The diesel and RON95 reforms have shown both promise and pain — leakages reduced, but household discomfort growing. The public now expects that the billions “saved” will translate into visible benefits: better schools, more reliable healthcare, stronger digital infrastructure, and food security that feels real, not rhetorical. Malaysians do not begrudge reform, but they do demand fairness and results. The government’s credibility now rests on how convincingly it can link fiscal savings to everyday well-being.

Budget 2026 is thus not merely a technocratic spreadsheet, but a story — one that must show Malaysia can consolidate without choking growth, reform subsidies without abandoning the people, and invest in innovation without losing sight of bread-and-butter realities. Whether the story convinces depends on how credible the allocations are, and how closely they align with Madani’s promise of governance rooted in compassion and sustainability.

Yet budgets cannot be read in fiscal isolation. They are social contracts measured by whom they empower.

So beneath this fiscal story lies a deeper social question: who exactly is “the middle class” that these policies aim to support?

Officially, Malaysia’s income pyramid is divided into B40, M40, and T20. In practice, this framework no longer reflects lived realities. The pandemic, inflation shocks, and uneven recovery have stretched and blurred these boundaries. The so-called “middle” is now far less secure than the label implies.

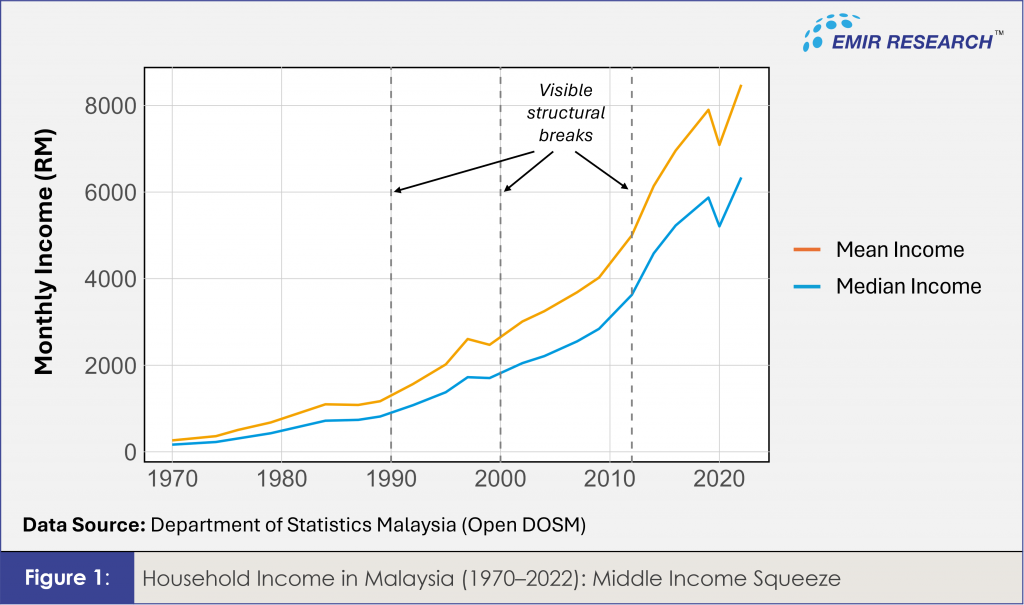

Data from the Department of Statistics Malaysia (Open DOSM) reveal the quiet truth: both mean and median incomes have risen steadily since the 1970s, but the gap between them has widened sharply, especially after the 1990s (Figure 1). That means national prosperity has grown increasingly skewed to the top. The rich are pulling the average up faster than the middle is moving — classic early sign of the “income squeeze”. After 2012, this divergence became structural, with the absolute cash gap — once just a few hundred ringgits — now amounting to several thousand.

Median income, which better reflects the experience of a “typical” household, has flattened in recent years even as costs continue to rise. The formal-sector median wage was RM3,000 as of March 2025, up 5.5 % year-on-year, but this increase barely keeps pace with inflation in food, rent, utilities, and childcare. Housing affordability remains out of reach for many: with median home prices hovering around RM280,000–RM330,000 and typical incomes between RM5,500 and RM7,000, the price-to-income ratio stands at 4.5–5.5 — well above the global affordability benchmark of 3.

Household debt adds to the pressure, now exceeding 84% of GDP, as reported by Bank Negara Malaysia (as of August 2025), among the highest in Asia. Savings rates are collapsing: Bank Negara’s 2024 Financial Capability Survey found that only 27 % of middle-income earners believe they could last more than six months on savings alone, while nearly 40% save RM500 or less a month. Many are one shock away from distress.

This pressure has also reshaped how Malaysians work. The move to dual incomes and side gigs is no longer a lifestyle choice but a coping mechanism in the face of stagnating wages and rising costs. A 2022 Remote Work Report found that 66% of Malaysian workers now have a second income source, signalling that this is not marginal but mainstream. Yet the formal share of part-time work remains low, suggesting that much of this effort takes place in the informal economy—freelancing, gig work, micro-enterprises—often without job security, benefits, or insurance. Qualitative studies (Khor & Mohamad, 2020) show that dual-income households face genuine role stress, work–family conflict, and emotional strain, meaning the “overwork” burden is far from hypothetical. What appears as economic resilience on paper often conceals household exhaustion and fragility in practice.

Even inside the “middle,” inequality is growing. The upper-M40 — with median incomes around RM10,552 — now behaves economically like the lower-T20, while the lower-M40, at roughly RM5,770, lives with little buffer. About 20% of M40 households fell into B40 status during the pandemic. The World Inequality Lab’s 2025 study using Malaysian tax data confirms that the M40’s income share is shrinking across multiple demographics.

Malaysia’s middle class is therefore less a cohesive block than a hollowed band: the top edge edging upward, the bottom slipping downward. The policy danger is clear — treating “M40” as a single group risks over-benefiting those already secure while neglecting those closest to vulnerability.

This is why EMIR Research proposes a recalibration of Malaysia’s household classification: from the traditional B40–M40–T20 to a more realistic B70–M20–T10 framework. The old B40–M40–T20 framework was drawn in a different economic era — before the pandemic blurred the lines of vulnerability and before inflation eroded real household thresholds. B70–M20–T10 structure would reflect the post-Covid income distribution, the softening of the global economy, and the contraction of true middle-class security. It would also make social protection more accurately targeted, allowing policymakers to tailor support and taxation with finer granularity. The lower M40 (or new upper-B70) is now where the squeeze is sharpest, and where policy attention should be concentrated.

Recalibration is not just semantics — it is a governance reform. It recognises that the middle 40% no longer has the resilience it once did. Under the B70–M20–T10 lens, fiscal tools such as targeted subsidies, tax relief, and social transfers can be recalibrated with greater precision. A more nuanced taxonomy also enhances the IOOI (Input–Output–Outcome–Impact) logic of public spending: inputs like tax savings or subsidy rationalisation can be more directly linked to outcomes that matter — improved savings rates, reduced household debt, and stronger financial resilience among the majority.

If Malaysia is to tell a coherent fiscal story in Budget 2026, it must begin by updating the very frame through which it sees its citizens. Fiscal consolidation without re-definition risks balancing the books while losing the public. Reclassification, grounded in data and realism, offers both moral and economic coherence: it aligns Malaysia’s fiscal architecture with its social realities.

Ultimately, the measure of Budget 2026 will not be how elegantly it manages the deficit, but how convincingly it rebuilds confidence among those who form the country’s backbone — the broad, hardworking Malaysians who no longer see themselves in the neat categories of B40, M40, and T20. Recognising them anew, as part of a dynamic B70–M20–T10 spectrum, is the first step toward restoring faith that reform and fairness can move together.

Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.