Published by The Asean Post, image from Malaysiakini.

There has been no closure to the Brexit issue since the 2016 Stay/Leave Referendum when the United Kingdom (UK) voted to leave the European Union (EU), until recently when British Prime Minister Boris Johnson won an outright majority of 80 parliamentary seats at last year’s general election on 12 December, 2019.

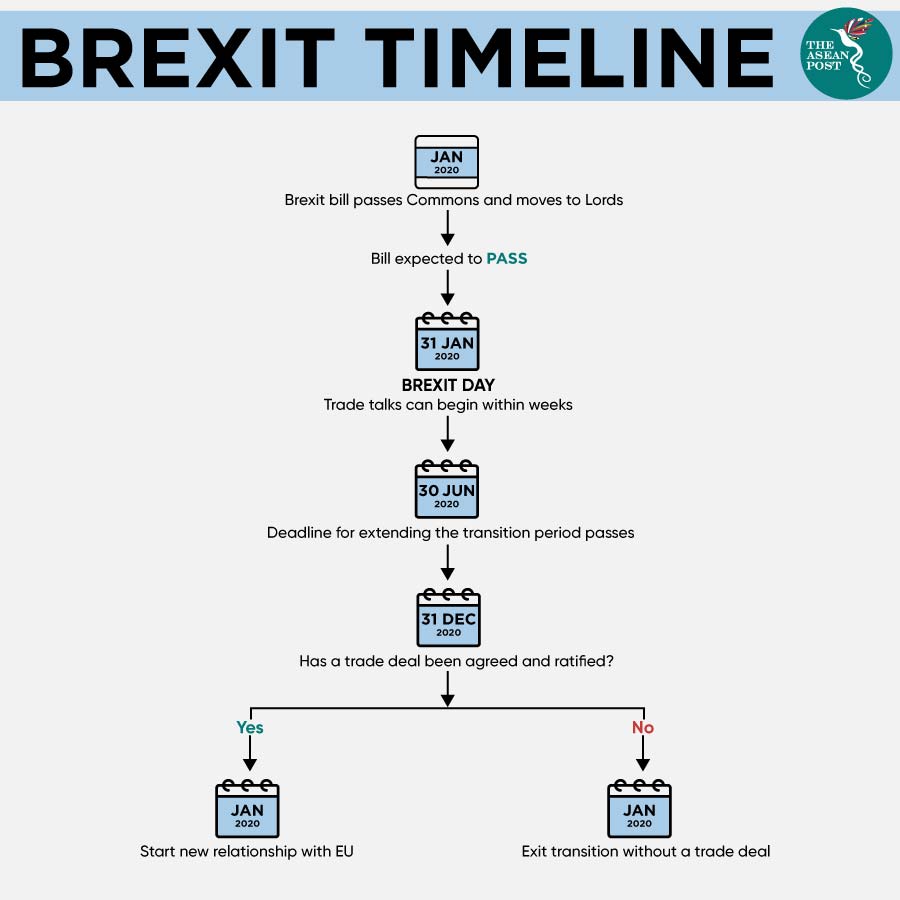

The result (which saw Labour’s working class support massively eroded) will enable him to pursue the strategy and objective of retrieving the UK from the EU as soon as practicably possible – by the deadline of 31 January, which is fast looming.

Much ink has been spilled about Brexit from both sides of the debate. This short article takes the position that Brexit is actually a good thing for the UK, and by extension the Commonwealth, among others.

When the UK acceded to the Treaty of Rome in 1957 via the European Communities Act of 1972, and hence officially joined what was then the European Economic Community (EEC) on 1 January, 1973, the “turn” towards Europe in general was inevitable.

In fact, since the winds of de-colonialisation was blowing across Africa and Asia, the UK particularly under Harold Wilson had been re-pivoting “back” to the European continent. The EEC was perceived to be the “emerging market” then – with a combined population of some 300 million.

Better still, the Common Market of the EEC offered access to UK businesses that provided a post-colonial alternative. It was therefore logical and natural at the time for the UK to have regarded Europe as the economic haven and indeed the future.

However, over the years, the Single Market had transmogrified into something beyond purely an economic or giant trading bloc. The four fundamental freedoms of movement premised on the establishment and existence of the Single Market had provided the very foundations for the move towards a political union – that is now known as the EU.

The Single European Act (1986), Maastricht Treaty (1992), Lisbon Treaty (2007), etc. have actually translated into more and more powers transferred to Brussels as the seat of power and de facto capital of the EU.

In other words, parliamentary sovereignty which lies at the heart of the unwritten or to be more precise, the now partially codified UK Constitution, has experienced significant erosion over time, even if unnoticed.

This is because according to section 2, 3, 4 and 5 of the European Communities Act (1972), parliamentary sovereignty is, in effect, subject to the supremacy of EU laws – as interpreted by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) from which there is no higher appeal to another body.

This had been vividly illustrated in the case of R v Secretary of State for Transport ex parte Factortame (No. 2) [1992]. In that case, both the High Court and House of Lords held that the Merchant Shipping Act (1988) was found to be in non-compliance with the EU Regulation on fisheries (as made under the European Council – not to be confused with the Council of Europe – that is represented by the heads of state and government of the member-states and is inter-governmental in nature).

Any legislation passed by the UK Parliament that is incompatible with an EU Regulation or Directive is null and void in terms of application, implementation or enforcement.

EU Regulations and Directives (among others) emanate from the unelected European Commission (comprising an elite cadre of ex-politicians and technocrats) which combines executive, legislative and semi-judicial powers within itself. The Commission, is therefore, the unrivalled and de facto seat of power and highest authority of all the EU institutions.

This means that the EU is no mere international or rather regional club or organisation like ASEAN or even the Council of Europe, as the promulgator of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

The judgments and rulings pronounced by the ECJ – as the inviolate arbiter and magisterium of EU laws – has been unquestionably clear as illustrated by cases such as NV Algemene Transport- en Expeditie Onderneming van Gend & Loos v Netherlands Inland Revenue Administration (1963) Costa vs ENEL (1964). The EU, therefore, claims outright or direct constitutional, legislative and judicial supremacy over member-states.

For otherwise, how could the EU function in the first place?

That is to say, without such primacy and supremacy of EU laws over domestic laws, how could the goal and objective of “ever closer union”, i.e. deep integration and assimilation (as per the Treaty of Rome, 1957) in the form of the four fundamental freedoms of (internal) movement as epitomised by the Single Market be met?

In short, in reality, as a result of EU membership, the UK had lost control over its own laws, money and borders in varying degrees.

That’s a fact.

And it’s a fact that the dream of the EU is for member-states to become more integrated and assimilated into its institutions and structures.

Some proponents even dream of a United States of Europe.

Perhaps the most famous figure of all is none other than the Hon. Mr Guy Verhofstadt MEP, the Brexit Coordinator of the European Parliament and former Prime Minister of Belgium (1999 to 2008) who has also written a book promoting the idea.

Conspiracy theorists go so far as to claim that the EU is none other than the Fourth Reich because it’s German-dominated and led. That is, what the Third Reich failed to achieve militarily was fulfilled economically.

Or even the supposed revival of the Holy Roman Empire that was breached as a result of the 16th century Reformation ignited by the German monk, Martin Luther.

Whatever it is, the EU super-project undoubtedly impacts on national sovereignty. Irrespective of whether national sovereignty is pooled, transposed or abnegated is not the issue. Ultimate political sovereignty, by default, no longer resided with the British people (democracy) but the European Commission (technocracy).

What made the British people become so fed-up, frustrated and disillusioned with the EU was finally the realisation of the economic impact, as highlighted by Nigel Farage (the erstwhile leader of UKIP and now of the Brexit Party and idolised by admirers as the UK’s best political communicator), rightfully or wrongfully, brought about by the influx of migrant labour to UK’s coastal towns.

This is why Boston, King’s Lynn, Margate, Hartlepool, Great Yarmouth, etc. voted to leave the EU in huge numbers, i.e. with resounding majorities. Places such as these have witnessed a rise in unemployment rate among locals (including youth). Arguably, the presence of EU migrant labour has undercut the local unskilled labour pool leading to wage compression.

On top of that, huge spikes in the immigrant population inevitably outpace the capacity of public services (primary and secondary healthcare, schools and social housing) to cater and accommodate at the local level.

Farage might have been a rabble-rouser but he did tap into the growing resentment and anger at the deleterious and enervating effect of the EU’s (unrestricted) freedom of movement of people which has to be said is heavily biased from Eastern Europe to UK, for example.

But what paved the way for the Brexit referendum was Cameron’s proposed renegotiation of the terms of the UK’s relationship in the aftermath of his Bloomberg speech in 2013. Basically, that speech 1) covered the UK’s future relationship with Europe; 2) called for fundamental reforms of the EU; and 3) proposed a Stay/Leave Referendum to be held on the UK’s membership.

Cameron’s renegotiation including attempting to secure the UK a “special status” was doomed to fail. As an aside, it could be argued that that the so-called “special status” actually re-emerged with a vengeance – or better still, ironically to be eventually embodied, finally, in the form of the EU Withdrawal Agreement Act (2018/2019) under Theresa May and Boris Johnson (2020).

Notwithstanding, Brexit will allow the UK to refocus her vision outwards, and re-orient towards the Commonwealth and the wider world once again. To renew her relations, and forge and foster trade and investment deals with fast-developing economies and emerging markets.

This means the UK will be able to take advantage of the grand horizons to expand her export markets alongside developing new supply chains and production networks, particularly in the context of the Commonwealth.

Brexit provides the golden opportunity for the UK’s economy to revive on the back of a re-balancing away from the EU and export its way round the world.

By extension, the UK’s post-Brexit economic renaissance could well be also a catalyst and impetus in the reinvigoration and renewal of the Commonwealth’s sense of purpose in the world.

The UK could then assume her rightful place in the world once again, as an outward-looking and self-confident nation. She can start harnessing her soft power and diplomatic prestige in service of the regained or newly found role in the world without the constraints and liabilities of EU membership.

Post-Brexit, the UK can be both, a global cum Commonwealth leader as well as strong and close partner of the EU in an increasingly uncertain and volatile world.

Jason Loh Seong Wei is Head of Social, Law and Human Rights at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.