Published by The Star and Business Today; image by Business Today

Malaysia’s debt debate remains trapped in numbers: 64 per cent of GDP, RM1.304 trillion, the statutory ceiling. Yet ceilings are political constructs, often gamed by guarantees and off-budget tricks (see “Debt, Deceit and Delay” by EMIR Research). The more vital question is not how high the ceiling sits, but how strong the floor is. What real fiscal space does Malaysia have once interest costs, rollover obligations, and household burdens are counted? And, crucially, what do we gain in return for every ringgit borrowed?

For too long, debt has been framed as either virtue or vice, when in reality it is a choice. The real test lies in whether borrowing strengthens or weakens sovereignty. Unproductive debt (bailouts, opaque guarantees, rent-seeking GLCs) drains public wealth and erodes trust. Productive debt—sovereign green bonds, food security investment, strategic technology scale-ups—builds resilience and generates returns. Debt itself is not the enemy; indiscipline is.

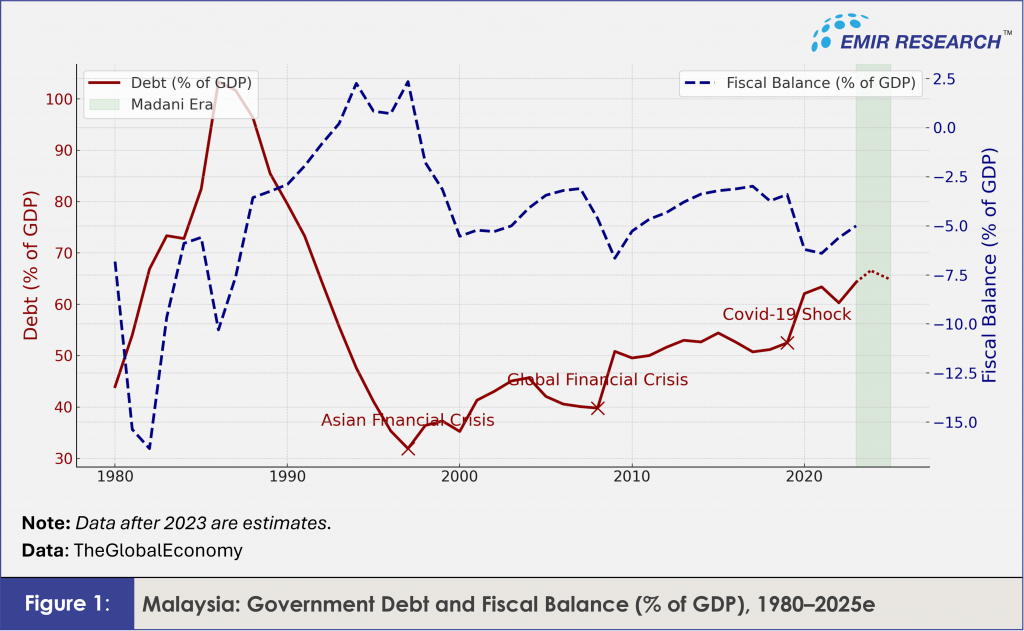

As Figure 1 shows, Malaysia’s debt trajectory follows a ratchet effect. Each crisis reset Malaysia’s debt to a higher plateau, narrowing fiscal space as deficits became structural since the mid-1990s as they persisted even in commodity boom years. This is why ceilings mislead: Malaysia is not experiencing an explosion, but a permanent high plateau that narrows fiscal space year by year. Without changing the quality of spending, the slope resumes upward by default.

That fiscal space is in fact even tighter than headline ratios suggest. Interest costs now consume a growing share of revenue, while legacy rollovers from past guarantees crowd the balance sheet. Add to this the pressing demands of subsidy reform and cost-of-living pressures, and it becomes clear that every new ringgit of borrowing must be justified not by convenience but by consequence.

Regionally, Malaysia already lags peers such as Indonesia and Singapore, but the real lessons, and the institutional fixes Malaysia needs, lie in how global reformers have embedded discipline. We can learn a great deal from countries that have not only tamed their deficits but also embedded discipline into the very architecture of public finance. These examples reveal what Malaysia still lacks—not just targets, but tools of genuine enforcement, credibility, and foresight.

Countries that have successfully disciplined their finances did so by anchoring budgets to rules that are clear, measurable, and binding—not just suggesting. Germany’s constitutional Schuldenbremse caps structural deficits at 0.35 per cent of GDP, while Sweden’s surplus target and debt anchor are embedded in its multi-year budgeting process. Even New Zealand’s Fiscal Responsibility Act forces governments to state prudent targets in law and justify deviations. Malaysia, by contrast, relies on a statutory debt ceiling that has been repeatedly raised and easily bypassed through off-budget guarantees. In practice, ceilings are political constructs rather than rules with teeth.

Enforcement only works when the scorekeepers are neutral. Around the world, effective fiscal frameworks are monitored by independent bodies that remove political bias from forecasts and compliance checks. Chile’s copper-based rule relies on an independent expert panel to estimate long-term prices, preventing governments from inflating assumptions. Sweden’s Fiscal Policy Council and the Netherlands’ CPB planning bureau publish neutral assessments that bind all parties. However, in Malaysia forecasts remain entirely within the Ministry of Finance, with only limited scrutiny from Parliament. There is no fiscal council or external body to validate assumptions or monitor whether the government actually meets its targets.

Fiscal health is not about year-to-year arithmetic—it’s about resilience across cycles and generations. Chile and Norway save resource windfalls in sovereign wealth funds, spending only the structural or investment return while keeping the capital intact. Singapore protects reserves constitutionally, drawing only the returns via its Net Investment Returns Contribution, while South Korea has built up massive foreign exchange reserves and a culture of fiscal prudence since the Asian Financial Crisis. Malaysia has no such buffers. Khazanah, EPF, and KWAP are investment and pension funds, not fiscal stabilisation tools. Petronas revenues flow directly into the budget, leaving the country exposed to every swing in commodity prices.

Real discipline also requires public accountability. In New Zealand, the Public Finance Act forces governments to publish long-term objectives, pre-election fiscal updates, and explicit explanations for any departures from their principles. Canada’s 1990s Program Review openly re-evaluated every federal function, prioritising essential services while cutting waste, which swiftly turned deficits into surpluses. Sweden too has embedded transparent multi-year processes that are published and debated in public. Malaysia, however, has no legal obligation to publish such forward-looking risk statements or to explain deviations from targets. Auditor-General reports exist, but disclosure remains patchy, politicised, and rarely tied to binding consequences.

Finally, the most durable reforms are those sustained across governments. Sweden’s surplus rule has survived left and right administrations for nearly three decades. Chile’s structural rule, for much of the 2000s, was respected across parties. Singapore’s budget balance requirement is hardwired into its political DNA. Malaysia has no equivalent consensus. Fiscal rules are rewritten with every coalition, subsidies are constantly re-designed, and reforms such as GST are easily reversed. This instability ensures that fiscal credibility is never locked in across political cycles.

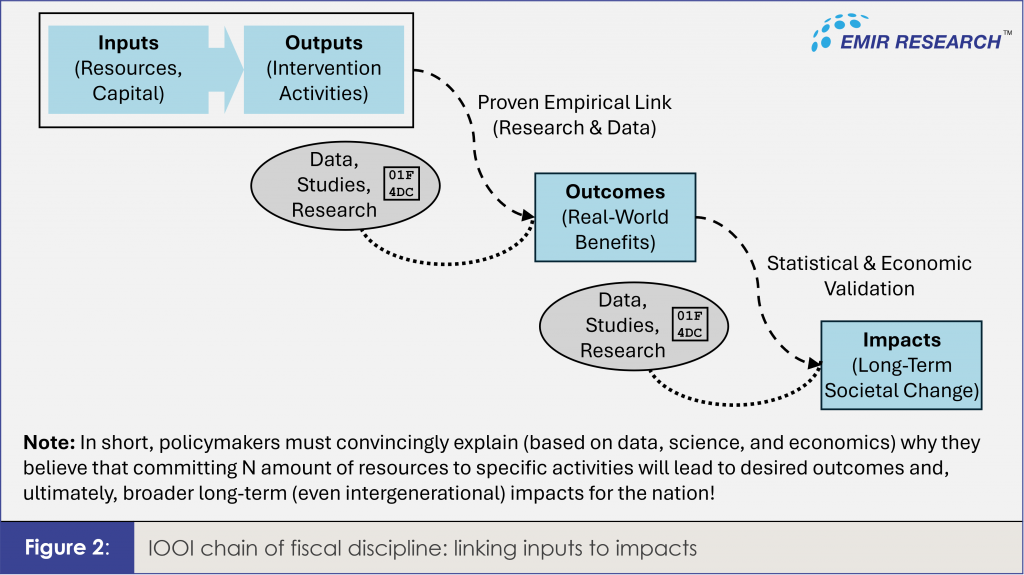

Apart from the above five pillars of fiscal discipline (rules with teeth, independent oversight, long-term perspective, transparency, and political continuity), the same countries also embedded what is, in essence, the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) approach — linking every unit of input to tangible outputs, measurable outcomes, and long-term impacts through data, science and economics (Figure 2). New Zealand’s Wellbeing Budget is a direct example: every intervention is tied to outcome indicators tracked over time. Norway’s and Singapore’s sovereign wealth funds are managed with IOOI-like discipline, where inputs (resource revenues) are transparently converted into global investments with clear performance and impact benchmarks.

In fact, IOOI is not a sixth pillar but the mechanism that underpins all five. It turns rules with teeth into enforceable commitments, gives independent oversight a yardstick, builds the bridge between inputs today and impacts tomorrow, forces transparency through measurable outcomes, and creates the shared evidence base that makes political consensus possible.

This is why EMIR Research has consistently argued (refer to “Transforming Malaysia from Third- to First-World Country”, 2021; “Recalibrating National Budget—Eradicating Leakages and Corruption”, 2022; “Reinventing Sovereign Wealth Fund: Let us be cleverer”, 2022) — that IOOI is the only way to close leakages and build intergenerational resilience.

Debt, too, must be placed inside this chain: every borrowed ringgit should be traceable from input to impact. Without IOOI, ceilings, rules, and funds become hollow. With it, they become tools of national transformation.

Malaysia does not need to copy Chile or Sweden wholesale. But it does need to absorb the principles that underpin their success: rules that bite, institutions that watch, buffers that matter, transparency that forces accountability, and consensus that endures beyond one administration. The IOOI framework can be the domestic tool to make this discipline measurable, linking every borrowed ringgit to outcomes and impacts.

The Madani government has only a narrow window to embed these reforms — to ensure that debt becomes not a ratchet of crisis, but a lever of resilience and sovereignty.

Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.