Published in The Star & Malay Mail, image by Malay Mail.

This is the third and final set of building blocks for a pandemic exit strategy—a series of publications initiated on 17 June, 2021 suggesting specific goals, strategies and tactics to complement recently announced steps by the government towards national recovery, whereby it aims to “exit” the Covid-19 pandemic in four phases.

In Part 1 of the exit strategy building blocks released on 17 June 2021, we also reiterated, using fundamental principles of economic theory, that the current pandemic-induced crisis is fundamentally different from past crises, which require a comprehensive strategic approach towards a gradual reopening of the economy.

Positioning its strategy in the uniqueness of the current pandemic-induced crisis, EMIR Research has suggested the following strategy based on 3 + 1 main strategic thrusts, which are:

1. Protecting lives and livelihoods

2. Education emergency response

3. National reconciliation

4. National economic recovery plan

Part 1 of the exit strategy building blocks, released on Thursday (June 17), elaborated on three main goals surrounding the immediate measures to protect lives and livelihoods alongside potential targets and success criteria.

Part 2, released on Friday (June 18), delved into two subsequent strategic thrusts—the emergency education responses and national reconciliation. These were developed with a critical focus on Malaysia’s circumstances and unique context that requires inclusivity and a whole-of-government approach.

The first three strategic thrusts described in Part 1 and Part 2 are all immediate short-term responses to eliminate the uncertainty associated with the pandemic as fast as possible and minimise the negative impacts on the rakyat.

While the last, fourth strategic thrust, which we discuss here, focuses on what can be done to stimulate economic growth immediately once the pandemic uncertainty is over and the economy can reopen at full or near full capacity on the basis that the first three strategic thrusts are followed through successfully – which could be at the start of 2022.

This strategic thrust is composed mainly of action items that would become fruitful in the mid-term to long term. However, their implementation must start immediately so that we are ready to stimulate the economy exactly when it is the right timing.

Fourth Strategic Thrust – National Economic Recovery

This strategic thrust has two main goals with corresponding objectives as outlined below.

Goal 1: Stimulating the real economy—use equitable income redistribution to stimulate the growth of economic activity by placing surpluses into the hands of those who need it the most and who have a higher propensity to spend for consumption.

In conditions of greatest uncertainty, surpluses (savings) by the wealthiest segments accumulated, for example, in banks and are channelled by banks not for lending purposes, but to the stock or foreign exchange market, which is in principle great for banks but does not meet the task of getting out of a recession.

Alternatively, banks could choose to distribute these surpluses to their choicest customers among Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) or household individuals, thus not benefitting those who deserve it and who could put this money into circulation, stimulating aggregate demand and fixed capital investment.

Unfortunately, even during a time of crisis the real economic sector is often at the mercy of the financial sector. But a nation must always keep the real sector in priority.

Economic recovery and growth require more than purely financial measures. For speedy economic recovery, it is essential to quickly reduce inequality and too strong stratification by the level of wealth, which also causes distrust to the authorities and between members of society.

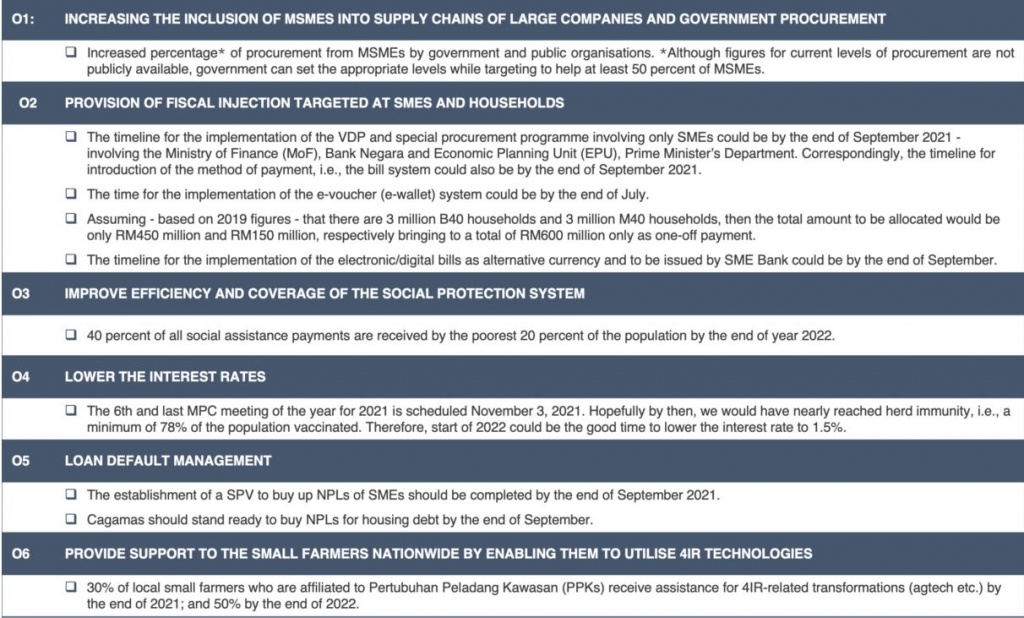

Objective 1: Increasing the inclusion of MSMEs into supply chains of large companies and government procurement.

This objective can be achieved by building a platform that can help MSMEs collectively bring their produce to the market and thus become competitive suppliers to large companies in the private and public sectors.

This may also necessitate subsidising logistics, transport and communication processes for MSMEs.

Even micro-enterprises should be included in this network. After all, the primary purpose of 4IR technologies is to give power and equal opportunity to the tiniest economic players.

Objective 2: Provision of fiscal injection targeted at MSMEs and households.

To build further on the above Objective 1, the government (public sector) should consider leveraging its role as the buyer and spender of last resort. This can be achieved by conceptualising the economy (understood as the private sector) into two parts, i.e., the MSMEs and households. Both sub-sectors have the same challenges of cash flow (shrinking savings, debt, reduced income).

The tactics involved here are the use of bills (for MSMEs) and e-vouchers (for households). Another advantage, other than no need to borrow, is the lack of worry over inflationary pressure/momentum.

The use of bills and e-vouchers means that these are not extra cash circulating in the economy all at once. But they represent government IOUs that take time to redeem. However, the circulation of these IOUs provides additional liquidity and stability to the real economic sector—it reduces the need for MSMEs and households to borrow while lubricating economic exchange transactions among them.

The Swiss Economic Circle (Wirtschaftsring-Genossenschaft), also known as WIR, is a successful case study of implementing a similar principle. WIR withstood the test of time since 1934 and provided greater stability to the Swiss economy and Swiss Franc for all these years.

Furthermore, now IOUs/e-vouchers can be created in the form of a blockchained ledger. Therefore, this practice will also promote a cashless society in line with the long-term vision and intention of the government, including its latest ambition that all government services are to go cashless by 2022.

Objective 3: Improve efficiency and coverage of the social protection system.

There is an urgent need to rebalance the distribution of social benefits payments to increase the coverage of the poorest and most vulnerable.

According to the latest assessment of Malaysia by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the 2021 Article IV Consultation, in Malaysia, around 30 percent of all social assistance payments are received by the poorest 20 percent of the population, which is significantly lower than in Asian and emerging markets on average. At the same time, in contrast to other countries, the population in the second to the fourth quintile receives a significantly higher share of total benefits than elsewhere, and almost 10 percent of the benefits payments are directed to the wealthiest 20 percent in the society.

These figures and comparisons suggest that targeting of payments should be improved, rebalanced and limited resources redirected to the B40 and lower M40 to increase the coverage of the poorest and most vulnerable households.

Objective 4: Lower the interest rates.

The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of Bank Negara has ample room to further lower the Overnight Policy Rate (OPR) from 1.75% to 1.5%.

But the timing is essential so that the monetary firepower can be effectively deployed under propitious circumstances. This concretely refers to the full resumption and reopening of the economy upon reaching >80 per cent herd immunity on a continuous basis, i.e., no more lockdowns are in view. Suppose the first three strategic thrusts (described in details in previous releases) are accomplished with achieving all targets on time; we can expect the appropriate time to lower interest rates in early 2022.

There is no danger of inflation as the output capacity as measured by effective demand (GDP growth) and level of unemployment remains below potential. In other words, spending has not reached a stage where it will outstrip the productive capacity of the economy in short- to medium-term. In fact, reopening the economy at full capacity should absorb some of the current inflation due to stimulus and imported inflation.

Objective 5: Loan default management.

Following the successful model of Danamodal dan Danaharta during the Asian Financial crisis, the government can establish a special purpose

vehicle (SPV) to take over bad loans of MSMEs (including in the tourism industry). This strategic tactic might become essential in the situation after the loan moratorium is lifted.

The government would assume the loans from the banks and turn these into soft loans – either interest-free or at 0.25% interest per year (but over a more extended repayment period).

The SPV, following Danamodal & Danaharta, could issue triple-A zero-rated coupon bonds to institutional investors such as EPF, Khazanah, pension funds, and insurance companies to be later exchanged for the NPLs from the participating banks.

Otherwise, the MSMEs could borrow from the government via the SPV to pay off (one-time) the banks concerned (again, either interest-free or at 0.25% interest and over a more extended servicing period).

Either way, the loans from the SPV will be collateralised by default unless otherwise agreed.

Asset restructuring for failed businesses in the tourism industry can be parked under the special tourism investment zones envisaged by the National Tourism Policy (2020-2030), which must be an immediate priority for the government. Participating players can be designated under these zones to also attract foreign funds as part of the effort to revive the tourism industry.

To help the households, Cagamas Bhd should be deployed to buy and take over non-performing housing loans.

Several options should be made available such as offering between zero and 0.5% interest rates to the house owners. This could stand alone or be packaged together with the implementation of its shared equity scheme – which has been in the works since the second quarter of 2019.

The scheme could be implemented by increasing Cagamas’ share of co-funding of the property from 20% to 40%. This scheme would then take place with immediate effect. This means the existing loan is converted into the scheme.

Objective 6: Provide support to the small farmers nationwide by enabling them to utilise 4IR technologies.

The spectacular success achieved by theMalaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC) in test piloting 4IR enabled small farming, where small chilli planters saw their yields increased by 33% and income by 22%, needs to be replicated and scaled up nationwide. A vibrant digital ecosystem, strong support from proactive stakeholders, practical policies, and an impactful framework is crucial to deliver impact at the national scale.

For this, the government does not necessarily need to invest on its own. The government’s job should be more supervisory—creating and ensuring a secure ecosystem where the interests of farmers would be protected without falling victims to the financial sector again.

A large number of farmers on the national scale enjoying higher incomes and collectively bringing their produce to the market would exert downward pressure on food prices, provided, of course, there is sufficient protection from foreign food suppliers.

Lower food prices would result in a lower food expenditure as a share of the overall household spending, thus leaving a larger portion of the national income available to be spent elsewhere. This shall undoubtedly stimulate the aggregate demand for other goods and services, fuelling national GDP.

Furthermore, implementing this objective could encourage youth (youth unemployment currently is high) to relook into the agriculture sector, which would also help address the second objective (O2) under Goal 2 of implementing structural changes discussed in this text below.

The following figure summarises the proposed targets for each of the above objectives to track the progress.

Figure 1: Targets and criteria under the goal of stimulating the real economy

Goal 2: Implement immediate structural changes– address inefficiencies at various societal levels that can be done promptly.

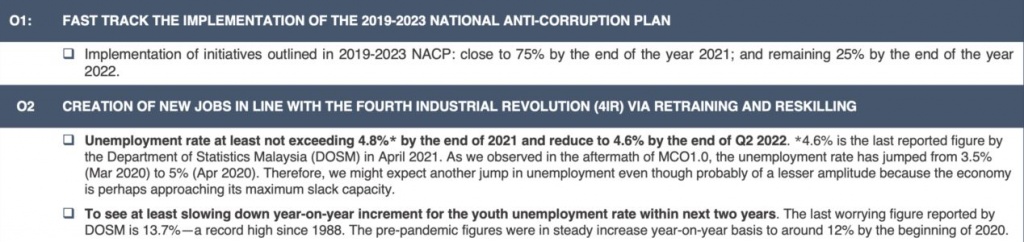

Objective 1: Fast track the implementation of the 2019-2023 National Anti-Corruption Plan (NACP).

Around a quarter of the initiatives outlined in the 2019-2023 NACP had been implemented as of end-December 2019—this is the latest available assessment according to IMF 2021 Article IV Consultation.

Even though NACP 2019-2023 designates four years for its implementation, given the current circumstance, it makes all sense to seek ways of fast-tracking this process.

Eliminating corruption at every level of society is the number one priority when limited financial resources need to be spent most efficiently and effectively (maximise the impact of every ringgit Malaysia spent). Failure to curb the spread of corruption will become a significant stumbling block in delivering on all the objectives under Goal 1 of achieving more equitable income redistribution.

Objective 2: Creation of new jobs in line with the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) via retraining and reskilling.

If Monetarists (neo-liberal) would expect employment to pick up as a result of monetary expansion (i.e., provision of cheap credit coupled with low-interest rate), we cannot expect such will be the case in the current situation in Malaysia.

Unfortunately, the current crisis coincides with some profound structural changes in the job market, and Malaysia is caught unprepared for it. Suffice it to say that youth unemployment has been on the rise for some time, even before Covid-19, due to skills inadequacy.

In the long term, only continuous investment in 4IR technologies and related skills at various societal levels (government, MSMEs, schools and universities) can address structural changes in the job market and reduce unemployment.

However, some immediate and quick win initiatives such as retraining and reskilling the existing workforce, especially those out of jobs, must be prioritised in the short term.

Figure 2. Targets and criteria under the goal of implementing immediate structural changes

The sequence of the four strategic thrusts released over the past days is in order of priority. However, the first three thrusts follow closely to one another and collectively determine when the economic measures mentioned herein can be embarked upon to maximise impact through the optimal use of limited resources.

Aligned with the notion that Malaysia is at “war”, these strategic thrusts guide all stakeholders (the authorities, politicians, private sectors and the public) to shift focus and unite towards clear priorities for the nation. It is not just a whole-of-government strategy but a whole-of-Malaysia approach.

With more and more people driven into poverty and lower-income brackets, and with the nation having limited resources and depleting reserves, Malaysia has a tight and demanding timeline to get this right, once and for all. Let us not make the blood, sweat, tears, and lives of the frontliners be in vain, nor allow livelihoods of the many to be destroyed while we can still do something about it. Malaysians must transcend societal divides, overcome selfish commercial greed and tame political desires to unite once more against an invisible, relentless, merciless and indiscriminate common enemy. The failure to uphold these priorities can and will drive the nation into a point of no return.

Dr Rais Hussin, Dr Margarita Peredaryenko, Jason Loh & Ameen Kamal are part of the research team of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.