Published in Astro Awani, TheStar, and MYsinchew, image by Astro Awani.

Malaysian brain drain appears to be getting from bad to worse. Yet, while designated government agencies and organisations put forward the initiatives to patch the growing void, the progress seems to be somewhat limited. This is because the programs aimed at reversing the flight of Malaysia’s human capital, as they stand, are too shallow to address the very fundamental elements the Malaysian expatriates set off looking for.

Since 1995, there have been “brain gain” programmes in Malaysia to attract our best talents back, but the results have been abysmal.

At one time, the Malaysian Employers Federation reportedly revealed that only about 50 (probably referring to the top talents) are returning a year. According to Talent Corporation, as of December 31, 2020 under its Returning Expert Programme, only 5,774 applications were approved from 2011 to 2020.

However, we have probably lost about 125,000 highly skilled over precisely the same period according to the estimates based on publicly available stats over the last 40 years (for estimates, refer to “Malaysian brain drain – don’t go chasing waterfalls”, May 24, 2022).

The question is: why the existing “brain gain” programs do not really work?

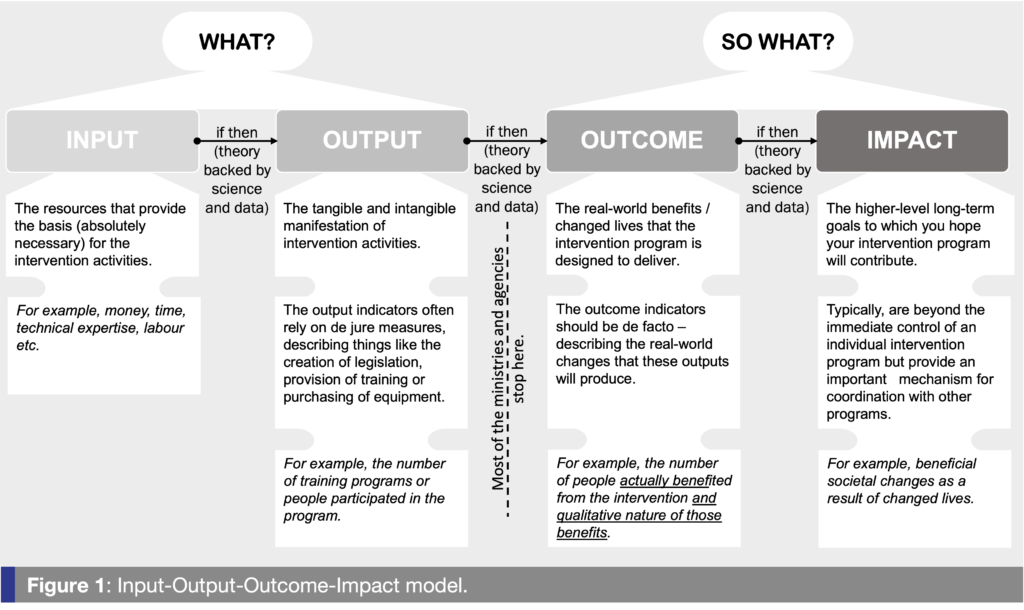

Generally, an impactful intervention program must be driven by data and science. There is a robust framework to design any impactful intervention program – Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) model.

EMIR Research has been long advocating the IOOI framework (refer to “Transforming Malaysia from third- to first-world country” and “Recalibrating National Budget – Eradicating Leakages and Corruption”) to be immediately institutionalised as an absolute requirement across all the government ministries and agencies if we want to move anywhere, in the right direction, as a nation.

To the benefit of the readers who are new to this concept, the IOOI framework (Figure 1) is logical and robust reasoning (solely based on science and data) of the entire causal path from inputs (scarce resources / capitals) to outputs (tangible and intangible manifestation of intervention activities) to outcomes (real-world benefits / changed lives) and finally to impacts (higher-level intergenerational goals, if we speak in the context of a nation).

In other words, when policymakers embark on an initiative, they must convince us, the public, that there is a solid basis in the form of empirical evidence and an established body of scientific knowledge to believe that spinning out an N amount of resources on specific outputs will result in the desired outcomes and intergenerational impacts.

Unfortunately, the normal culture in all the government agencies and ministries in Malaysia is to stop at the output stage only. There is no general feeling of need to check whether the outputs – those intervention programmes they design – are even linked to the desired outcomes through the accumulated data and empirical findings.

Currently, Malaysia’s “brain gain” programs are mainly centred around salaries and other benefits.

However, in “Malaysian brain drain – don’t go chasing waterfalls” EMIR Research has presented the detailed results of a meta-analytical review of academic research on brain drain in the Malaysian context over the last decade — the long list of various “push” and “pull” factors that have been empirically linked to the Malaysian brain drain.

Out of this list, attractive salaries and other benefits constitute a minuscular fraction. But how about that long list of other factors related to adverse economic climate and culture, lack of innovation, lack of excitement from newness and progressiveness, high rigidity, hierarchy, extreme conservatism, lack of meritocracy, but overabound of complacency, corruption, social injustice and outright racism at times etc. which were all linked, as “push factors”, to the talented Malaysians leaving the home country?

The core underlying problem behind all of these factors is poor governance, poor policy planning and/or execution (biased, corrupted, populistic, suboptimal, identity-based, divisive, haphazard, unfair, inconsistent, complacent, incompetent, regressive and simply outdated), which, as EMIR Research already underscored, is the single most critical variable we need to change before we see might start seeing the brain drain reversal.

In the same vein, evidence already suggests that for the Malaysian brain drain, this is no longer about the high salaries and perks.

As revealed in the details of the yearly published Critical Occupation List by TaletCorp, the vacancies for occupations that require high skills and knowledge related to ICT, electronics, engineering, and research have been difficult to fill since 2015/2016 to date, even when the employers offer higher salaries to attract the critical talents. Also, as some employers disclose, there is steep competition for these vital occupations from abroad.

Another recent statistic from Randstad (global HR research) revealed that in Malaysia, 64% of respondents want a safe work environment, while 52% want the opportunity to do meaningful work.

It is an interesting question though how do you define a “safe work environment”. However, it shall not be far from an environment where all the decisions are made based on merit and credibility. And if we recall all those “push factors” such as lack of meritocracy again, but overabound of complacency, corruption, social injustice and outright racism, that does not sound like a safe work environment at all.

Furthermore, 52% want the opportunity to do meaningful work – they want to make an impact. But how can you make an impact in an environment where there is no planning for it in the first place? Remember the pervasive culture of stopping at the input-output stage mentioned above?

Meanwhile, currently, millennials (those born between the 1980s – 2000s or those in their early 30s/40s) are the largest population (and workforce) cohort in the world, including Malaysia, and they have some significant preferences, as numerous empirical findings on this group suggest. They look for impactful work (they want to make an impact on society) above anything else (even salaries and perks). They look for empowerment and purpose in their work environment as opposed to rigidity and climbing the long hierarchical organisational ladder.

However, with those push factors, we listed just now, very likely, not many millennials can find a satisfying work environment in Malaysia—with high rigidity, hierarchy, extreme conservatism, being stuck in mid-80s solutions, in the complete absence of IOOI.

This is why we should expect millennials to be the significant flock among our diaspora. And they are going and making an impact on other nations. Not to forget that it is mainly the millennials who create start-ups, again, because of their intrinsic orientation on the social impact.

The Malaysian brain drain is likely to intensify even further in the forthcoming prominent workforce in the face of generation Z (pure digital natives), who are even more attuned to instant gratification, results and impacts.

And until policymakers continue to ignore all of the above findings based on data and science on the root causes of brain drain, the programs they design to return our highly skilled and talented expatriates will be akin to using a pail of water when your entire house is on fire.

We want to return them – we need to immediately jump on massive structural reforms in our country to ensure a high level of inclusiveness, strong institutions and a high level of coordination between social (need-based) and industrial policies (merit-based).

Rais Hussin and Margarita Peredaryenko are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.