Published by AstroAwani, image by AstroAwani.

Innovation drives a nation’s progress. Throughout history, our ability to rapidly create and implement solutions has shaped human development. These innovations not only enhance problem-solving efficiency but also fuel economic prosperity through their widespread adoption. In essence, keeps us competitive, especially in the 21st century.

In Malaysia, our focus on innovation appears to have taken a backseat, reflected in our stagnant ranking on the Global Innovation Index (GII).

It is important to note that the GII 2023 data mainly draws from 2021 and 2022 (34% and 35%, respectively). Additionally, the GII undergoes frequent methodology changes in certain pillars and indicators, such as transitioning from an index to survey questions for the sub-indicator “finance for startups and scaleups.”

While analysing year-over-year changes becomes challenging (and GII itself does not recommend it), gaining insights into recent years and short-term trends remains valuable.

The most recent report indicates an increase in Malaysia’s GII score—from 38.7 in 2022 to 40.9 in 2023—breaking a five-year decline since 2018. Yet, this score increase may not fully reflect Malaysia’s innovation performance.

In GII 2023, Malaysia made significant progress in the “market sophistication” pillar, ranking 18th globally. This improvement was driven by a score of 53.2 for the pillar, representing a 7.9-point increase compared to GII 2022. Yet, this performance still falls short of our pre-pandemic levels. The change in methodology, particularly the increased focus on venture capital-related index in the “investment” sub-pillar, likely contributed to this shift.

Despite the positive trend in venture capital investments (with both investors and recipients increasing to 0.1 deal per billion PPP$ USD) and growth in the domestic market scale, there is not much change in other sub-indicators. Notably, the “finance for startups and scaleups” has shown substantial improvement, but due to changes in methodology for the sub-indicator and reliance on older data, it remains unclear how much overall progress (if any) has been made.

In the GII 2023, another notable improvement was the increase in average R&D expenditure by the top three global corporations. Specifically, this spending rose from zero (as reported in the GII 2021) to USD 44.2 million. However, it’s essential to recognise that this surge aligns with the post-pandemic recovery period (around 2022 when Malaysia just began recovering from the impact of Covid-19), and the increased R&D spending merely reflects a return to the pre-pandemic levels.

Despite our input ranking rising to 30th—our highest since the GII 2014—with improvements “business sophistication” pillar, our output ranking tells a different story. It plummeted to 46, making our lowest rank between 2013 and 2023.

Despite minor improvements in both output pillars compared to GII 2022, the substantial decline in our output ranking is justifiable. Our score in the “knowledge and technology output” pillar has hovered between 31 and 33 since GII 2016. However, our “creative output” score in the GII 2023 is the second lowest, just slightly ahead of the GII 2022.

Even after considering the change in methodology, our ranking (i.e. comparison to other countries) still falls among the lower end. This suggests that we’re grappling with the challenge of keeping up with the impressive progress by other nations.

For example, in the GII 2023, one notable sub-indicator was “mobile application creation per billion PPP$ GDP,” which measures global mobile app downloads based on the origin of the developer’s headquarters. Despite our score skyrocketed to 63.1 per billion PPP$ USD (the second-highest after 11.4 in GII 2018), our ranking slipped from 66th to 74th place compared to GII 2022, where we scored 2.5 on this sub-indicator.

There are many factors that contribute to our inability to keep up with other countries in terms of innovation, including financial investment, human capital development, and efficient resource utilisation.

In a past publication examining Malaysia’s position in GII 2022, EMIR Research highlighted issues related to our utilisation of research talents and our financing capabilities (refer to “Malaysia’s Position in the Global Innovation Index: False Comfort Risk?”). Interestingly, despite our financial investments being on par or even improving in recent years, our global brand value among the top 5,000 brand has declined. Consequently, it is no longer one of our strengths, and we have fallen out of the top 10.

This could be an indicator that local brands have not been able to effectively access the resources necessary for their innovation progress.

According to the GII 2023, Malaysia’s performance in both the institutions and infrastructure pillars has declined.

Within the “institutions” pillar, our scores for the “institutional environment” (which assesses government stability and effectiveness) and the “regulatory environment” have decreased. Notably, the GII 2023 evaluates these sub-indicators using data from 2021, a period when Malaysia faced a political crisis.

As for our infrastructure, we are witnessing not only a decline in the utilisation of information and communication technology (ICT) but also ecological sustainability. While ecological concerns are important, it is the lack of ICT infrastructure utilisation that stands out. Despite a growing number of ICT users, accessibility remains low, e-participation is limited, and government online services have decreased.

The decline in both pillars could signal reduced effectiveness and efficiency within government agencies under previous administration, considering the timing of the underlying data.

Although our performance in human capital development improved across all sub-pillars in GII 2023, closer examination reveals no cause for celebration. These gains primarily stem from mere increased expenditures, including higher government spending on education and the aforementioned global corporate R&D expenditure— essentially “input” indicators.

Among other sub-indicators, our teacher-to-student ratio has slightly decreased (lower is better). However, this decline may be attributed to the reduced new student enrolment, as our annual live births have been decreasing since 2014—not necessarily due to an increase in the number of teachers (Department of Statistic Malaysia (DOSM), 2024). Furthermore, there’s a growing trend of teachers opting for early retirement (Malay Mail, 2024).

In higher education, although our graduates in the science and technology sector increased, maintaining a top-10 global position and even ranking 1st in GII 2023, the limited impact on our output can be mainly attributed to brain drain.

Brain drain has long been an issue in Malaysia, with people leaving our country for various reasons, including salary and job prospects (Refer to “Malaysian Brain Drain: Voices Echoing Through Research”).

The persistent issue of brain drain may explain the decline in multiple sub-indicators—both input and output. These include patents by origin (from 1.2 per billion PPP$ USD in GII 2019 to 0.9 in GII 2023), research talent in business (from 21.9% in GII 2019 to 15.8% in GII 2023), and the number of researchers we have (from 2,357.9 full time equivalents/FTE per million population in GII 2019 to 2,184.7 in GII 2023).

This is even without taking into consideration how our overall PISA score has dropped in 2022 assessment, raising concerns about the quality of our graduates. Employers are increasingly sceptical about local graduates (Refer to “Overqualified for Their Jobs, or Underqualified as Graduates?”).

Furthermore, there appears to be a growing trend among our youth—losing confidence in our education system—which has led to lower tertiary enrolment rates, especially since the pandemic era. Rising living costs, low starting salaries in relative to the cost of living, and the financial burden associated with pursuing higher education have pushed more young people towards early employment (Refer to “SPM absenteeism: The end result of mismatch between education sector and job market”).

Addressing the significant mismatch between education and occupational needs is crucial to rebuild trust in our education system. Achieving this will necessitate a comprehensive reform of the education sector, aligning our schools with global educational trends and elevating the standard for our future generations (Refer to “Urgent Need to Reform Malaysian Education System”).

On the other hand, Malaysia consistently performs well in financing-related sub-indicators over the decade of GII evaluations. However, the lack of effective checks and balances has made government spending susceptible to leakages—whether through spending it on random outputs (not linked, through data and science, to sensible outcomes and impacts for the nation) or misappropriation.

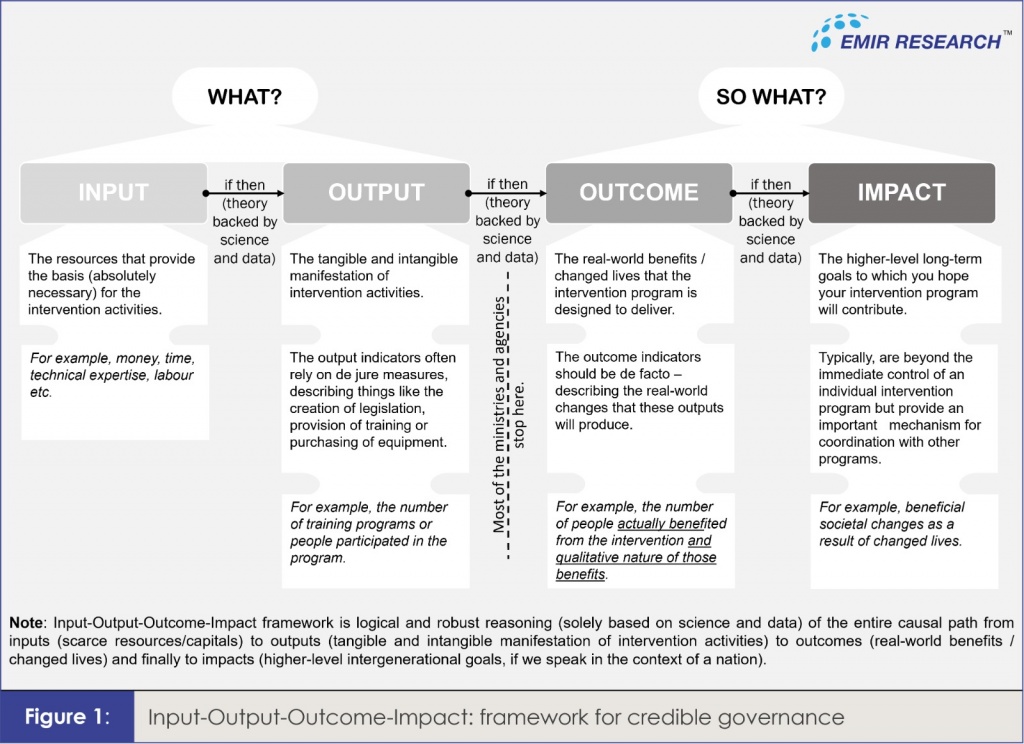

A recent audit report revealed a massive scandal involving the Human Resource Development Corporation (HRDC), implicating hundreds of millions of Ringgit. This underscores the unsustainability of outdated budgeting and spending practices (Malaysiakini, 2024). EMIR Research has consistently advocated for the adoption of the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) framework (Figure 1) across all government and government-linked entities—a crucial step towards credible policymaking, including in the realm of innovation (refer to “Recalibrating National Budget – Eradicating Leakages and Corruption”).

IOOI is well-suited to assist the current administration in its efforts to achieve more responsible spending. IOOI framework is hugely popular in the countries acing the GII.

Responsible spending would significantly strengthen our performance across various output, outcome and impact GII indicators, including in the sub-indicator “firms offering formal training”. Regrettably, it’s currently flagged as one of our weaknesses. Consistently, our employers repeatedly cite training costs as a barrier to providing such opportunities for their employees (The Star, 2023).

As the GII 2024 (calculated based on more recent data) is expected to be released in the next two months, we anticipate improvements in our output score. The reason behind this lies in the AI boom that started in late 2022 and continued into 2023 under the concerted effort by the current administration. This boom has driven growth in our semiconductor industry and the expansion of data centres, thereby boosting our high-tech manufacturing and export capabilities, including ICT services.

Additionally, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s efforts in attracting high-value FDI from around the world, which if successfully realise, are poised to positively impact both our input and output ranking in the GII 2024 and beyond. Only the government needs to implement IOOI model more broadly and systematically as part of ongoing institutional reforms!

Some policy changes, especially those related to education, take time to have an impact. For example, a curriculum change would take years before students affected by the change enrolling in tertiary education, let alone significantly influence our innovation output in a short period of time.

Our lag in innovation output stems from past poor policy design and implementation. Without broader/systematic IOOI-driven changes continuation, our current momentum will dissipate, as we will soon lack the human capital needed to utilise funds to improve or maintain our output.

Chia Chu Hang is a Research Assistant at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.