Published in Astro Awani , image by Astro Awani.

Aside from the lowest overall voter turnout of 53.6% in the Johor state election, there were 25,953 rejected votes across all the (contested) state constituencies. Although the total number of rejected votes only consisted of 1.82% of all the ballot papers issued (1,426,573), nonetheless, this could have diminished the winning chance of the candidate – indirectly affecting the overall electoral outcome (in that particular constituency).

Rejected votes (undi ditolak) are simply ballot papers that had been placed into the ballot box but not accepted for the final tally.

Image 1 shows situations where ballot papers are regarded as rejected votes:

Top left: X symbol on top of the candidate’s name;

Bottom left: Marking two candidates with two “X” symbols;

Top right: X mark in between the candidate boxes – not exactly in one box; and

4. Bottom right: Circle instead of making the X symbol.

Image 1: Example of rejected votes

Source: PRU 14: Contoh-contoh Kertas Undi yang Rosak/Ditolak, Aynora Blogs, April 16, 2018, https://www.aynorablogs.com/2018/04/pru14-contoh-contoh-kertas-undi-yang.html

At the end of the day, if the polling station head (ketua tempat mengundi/KTM) rejects the ballot paper, the actual or proper term is known as rejected votes instead of spoilt votes.

On the other hand, spoilt votes (undi rosak) are ballot papers that were never put into the ballot box in the first place. The ballot paper may have been crumpled, torn or simply defaced and the voter could have asked for a new one as replacement.

However, political parties, candidates, media and the public are often confused about the difference between rejected votes and spoilt votes or simply unaware of the technical distinction.

Johor witnessed around 200 rejected votes in all contested state constituencies, on average. This could well indicate that there is a serious possibility that some Johoreans may have been somewhat ignorant of the correct way to mark one’s voting intention.

However, there were also cases whereby the voters concerned would have been aware of the proper voting method, but decided to purposely mark in a way that would be considered as rejected votes.

Two plausible scenarios arising from this:

Public dissatisfaction and anger that the incumbent has been dropped or that the selected candidate is not the preferred choice (i.e., misalignment in preference between party and candidate) and thereby the rejected votes;

Voters had no idea which candidate to choose from but still wish to fulfil their civic duty. For example, a voter might be torn between two candidates as the preferred choice. And so, the outcome is that the voter then ended up marking both the two candidates with the “X” symbol, respectively.

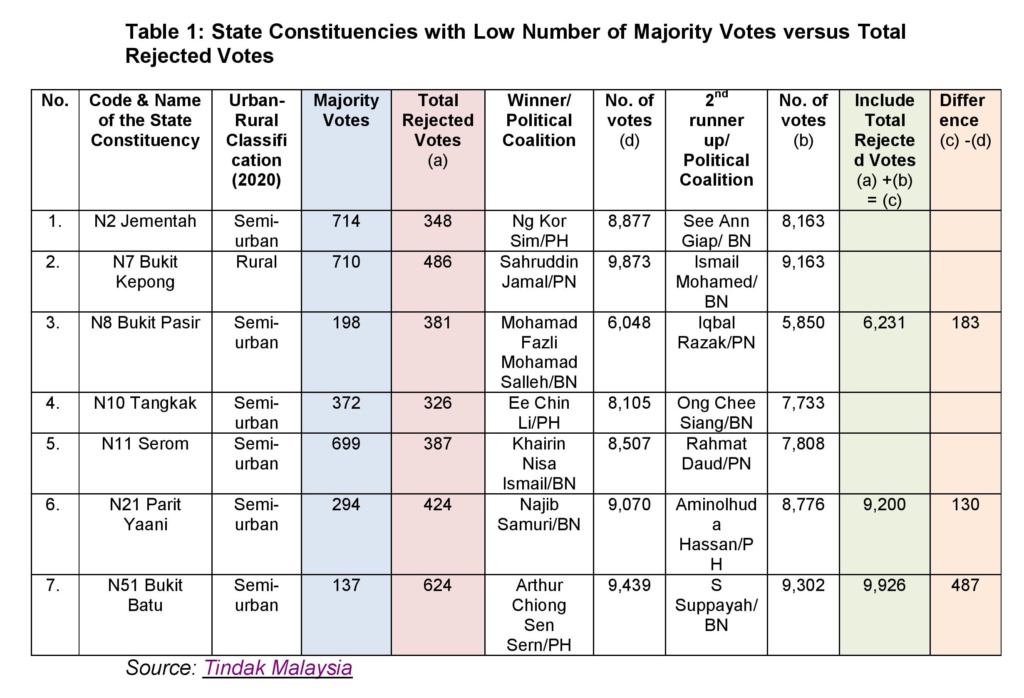

Let us now look into the state constituencies with less than 1,000 majority votes (as shown in Table 1).

It is especially striking when we look at those state constituencies with a higher number of total rejected votes when compared to the majority votes.

Firstly, Mohamad Fazli Mohamad Salleh and Najib Samuri from Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition only managed to win 198 and 294 majority votes in Bukit Pasir and Parit Yaani state constituencies, respectively. On the other hand, Arthur Chiong Sen Sern from the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition received only 137 majority votes in the Bukit Batu state constituency.

Secondly, when we combine the number of votes gained by the 2nd runner up with the total rejected votes per state constituency, Iqbal Razak from Perikatan Nasional (PN), Aminolhuda Hassan from PH and S Suppayah from BN could have won Bukit Pasir, Parit Yaani and Bukit Batu by 183, 130 and 487 votes respectively. By implication, it would mean that:

BN would have managed to only clinch up to 39 state seats – that is, the 40 seats actually won by BN minus Bukit Pasir and Parit Yaani (assumed lost to PN and PH, respectively) plus Bukit Batu (assumed won by BN);

PN could have won another seat – thus adding up to four state seats; and

PH would still have been able to retain 12 state seats, irrespective.

Notwithstanding, state constituencies such as Jementah, Bukit Kepong, Tangkak and Serom are in a safe position – the total number of rejected votes is lesser than the majority votes. However, if these constituencies have a higher voter turnout rate, there is a possibility that the total rejected votes could surpass the amount of the majority votes. This is particularly true for the Tangkak state constituency, with only 46 votes difference between the majority votes and total rejected votes.

Tindak Malaysia – a Malaysian movement dedicated towards awareness, empowerment and mobilisation for electoral reform – revealed that Jementah, Bukit Kepong, Tangkak and Serom experienced a relatively lower voter turnout rate at 53.73%, 61.01%, 56.95% and 58.05%, respectively.

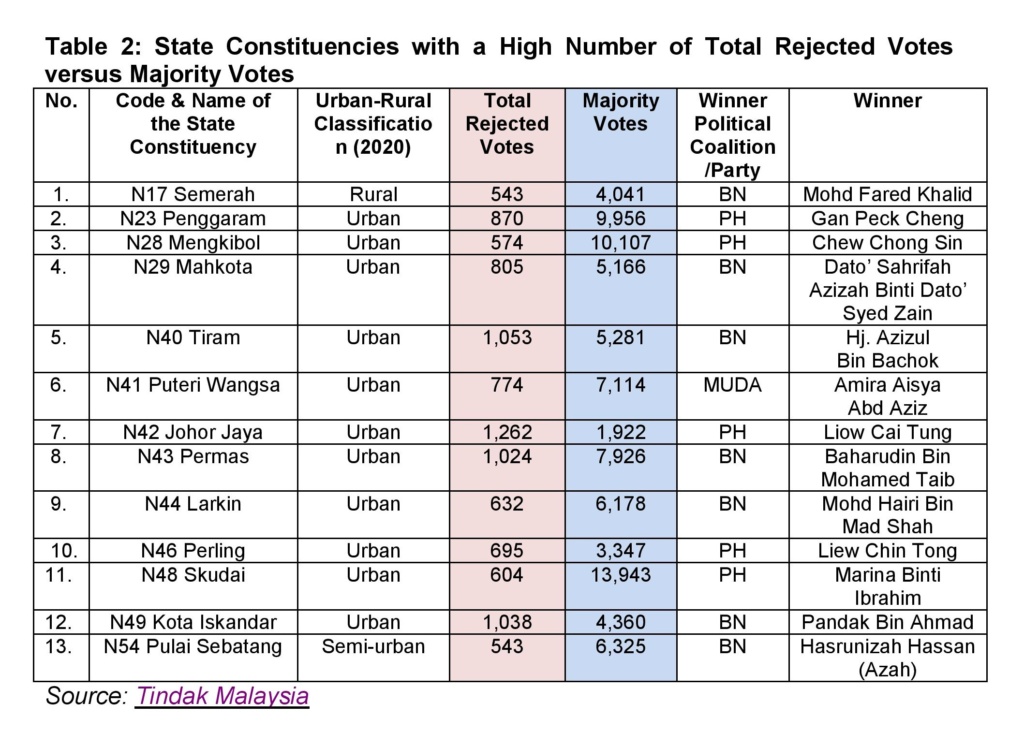

Let us also look into state constituencies with over 500 rejected votes in Table 2.

We can see here that the state constituencies nearby Singapore like Tiram, Johor Jaya, Permas and Kota Iskandar recorded over 1,000 total rejected votes. Nevertheless, Liow Cai Tung from PH, Hj. Azizul Bin Bachok, Baharudin bin Mohamed Taib and Pandak bin Ahmad from BN managed to win their respective contested state seats as their majority votes were higher than the total rejected votes.

But if Johor Jaya experiences a voter turnout higher than the overall 53.22% at the election, it is quite possible that Liow Cai Tung may not have been able to win at all. Chan San San from BN possibly could have outperformed Liow. Chan received 17,860 votes – a small difference from Liow’s by 1,922 votes.

Another interesting trend is that most state constituencies with over 500 of total rejected votes are in the urban areas. This correlates with scenarios 1 and 2 identified in this analysis – that the phenomenon of rejected votes are mainly from the urban voters.

Still, when it comes to Semerah, Penggaram, Mengkibol, Mahkota, Puteri Wangsa, Larkin, Perling, Skudai and Pulai Sebatang, these seats are relatively strong for the winner as the majority votes received are more than 3,000 votes.

Notwithstanding, Mengkibol and Skudai recorded lower voter turnouts of 51.92% and 44.87% than the average. Yet, Chew Chong Sin and Marina Binti Ibrahim from PH won over 10,000 majority votes in their respective state seats contested – at 10,107 and 13,943 votes, respectively.

With the 15th General Election (GE15) just around the corner, the government, political parties, media authorities and civil societies have to constantly educate Malaysians on the process and way to vote.

Ongoing initiatives to spread awareness on the importance to vote would eventually let more Malaysians appreciate why their votes matter.

At the same time, more Malaysians would recognise the correct way of voting by putting only one “X” within the empty box beside the candidate’s name and party symbol (as shown in Image 2).

Image 2: Example of accepted vote

Source: Bersih 2.0, 2018

When more Malaysians can identify what constitutes a spoilt or rejected vote, they could make the right choice about which candidate to vote for – indirectly reducing the number of spoilt or rejected votes in the next elections to come. Lesser spoilt or rejected votes are also an indication that political parties and candidates would have a higher chance to win their desired state or parliamentary seats.

Amanda Yeo is Research Analyst at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.