Published by AstroAwani, image by AstroAwani.

Malaysia’s political landscape has experienced noticeable changes due to the increasing popularity of the Internet and social media platforms. Remarkably, it has changed the strategies of politicians and political parties for election purposes and dissemination of information, often not in the nation’s best interest.

Indeed, the Internet has profoundly transformed the global community, fostering economic growth, instilling robust governance structures and systems, democratising information access, and empowering MANY through digital flexibility.

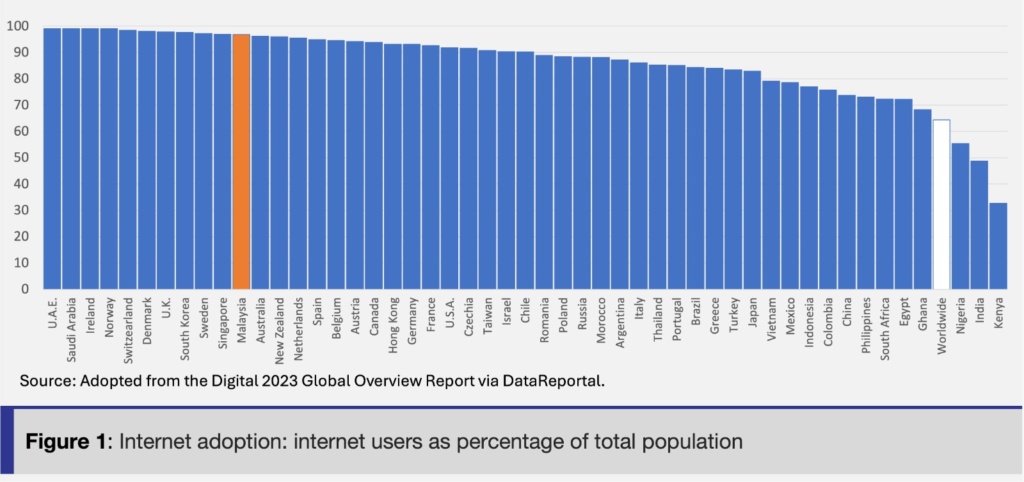

According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), as of 2022, 97.40% of the Malaysian population has Internet access, marking a substantial increase from 56% in 2013, placing Malaysia at par with the most connected (and concurrently the most developed) nations, as per the Digital 2023 Global Overview Report (Figure 1).

The report and other global data also show that Malaysians experience affordable, high-quality mobile internet relative to their income level (refer to “Malaysian 5G Rollout—Bending the Truth Like No Other” for statistics).

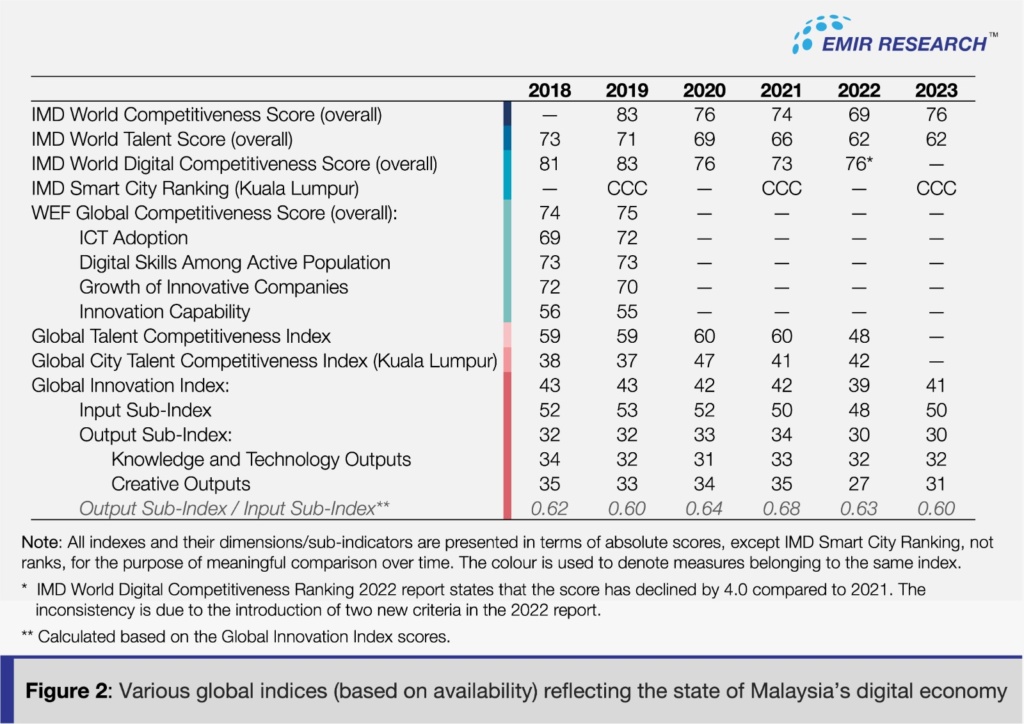

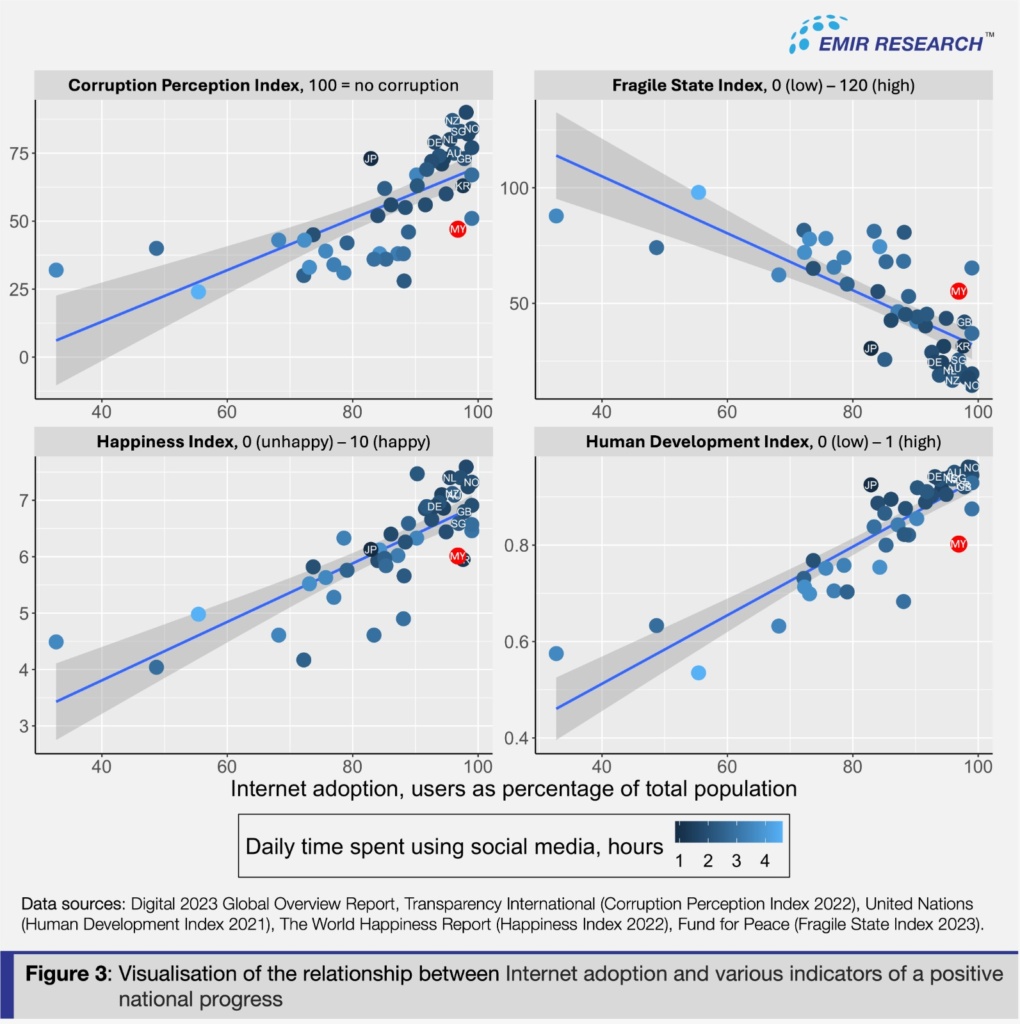

Yet, unlike in the most developed nations, enhanced connectivity in Malaysia did not translate into increased productivity, sensible nationwide outcomes (note the decline or, at best, stagnation in Figure 2), and positive intergenerational impacts (Figure 3).

The report shows that quite the opposite to the developed nations, Malaysia spends extensive time online, particularly on social media, where consumerism, small talk (about self or others), cybertroopers, and other unproductive activities we know are prevalent.

Furthermore, most of the social media use by Malaysians is not for work, and nearly 43% of its users (among the highest in the world) use it as a news source. At the same time, paradoxically, almost 64% (again one of the highest figures globally) are concerned over misinformation online.

Inevitably, strategists from all walks of life (business or political domains) find it increasingly advantageous to use this very “fertile ground” to advance their personal interests, company/party objectives, or national interests by deploying cybertroopers on social online platforms.

The cybertrooper community in Malaysia plays a crucial role in electoral activities. It comprises party members, political activists, unaffiliated supporters, and other social media influencers, making it a significant component of electoral strategies.

As a critical component of the digital strategy, cybertroopers significantly influence public opinion through online forums, blogs, and social media platforms, thereby influencing election results and shaping public opinion by sharing memes, images, and videos, among various forms of manipulative and deceptive content online.

The 2020 Oxford Internet Institute media manipulation report identified Malaysia as one of 81 countries where misinformation is operated on an “industrialised scale” by well-organised cybertrooper teams involving governments, public relations agencies, and political parties.

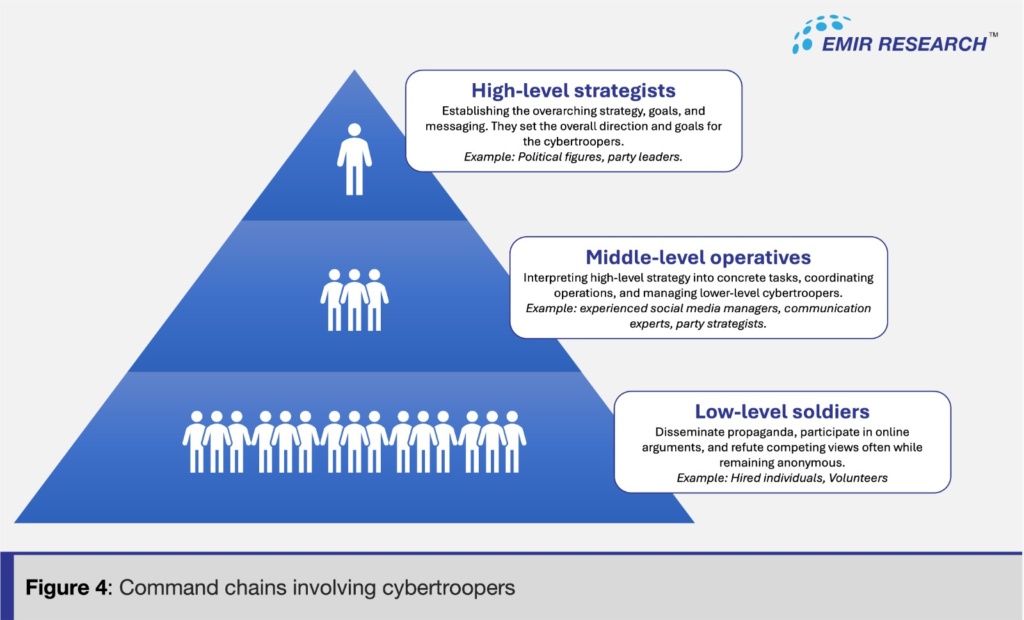

Cybertroopers are individuals who are paid to disseminate pro- or anti-government or party propaganda, attack the government or opposition in smear campaigns, and suppress participation by other network users through personal attacks or harassment on the Internet, particularly on social media platforms (the command chain structure is in Figure 4).

For instance, in her book “Digital Mediatization and the Sharpening of Malaysian Political Contests”), author Pauline Pooi reveals that before the 14th General Election (GE14), Najib’s administration deployed 4,000 cybertroopers. Their roles included countering opposition, policy promotion, and online psychological warfare. Compensation was tied to their expertise, ranging from hundreds to millions in Malaysian ringgits.

Cybertroopers use fake or compromised accounts to manipulate the political loyalty of social media users, exploiting their psychological weaknesses. In the process of engaging in back-forth online discussions with cybertroopers, the rakyat unwittingly becomes “keyboard warriors” in amplifying the outreach and aiding those with malintention in shaping public opinion for the gain of their masters. This poses a severe challenge to Malaysia’s democracy.

Cybertroopers seriously distort the “truth layer” or crucial feedback loops between the government and the public, which are essential for a well-functioning society — building trust in officials and holding those in power accountable. This greatly harms the nation and hampers the work of civil society organizations.

The rise of cybertroopers during the recent Malaysian general, state, and even, to an extent, by-elections poses a significant threat to the electoral process, integrity, transparency, and the parliamentary system’s stability.

Some of the recurring patterns of disinformation browbeaten in cyberspace, frequently politicised by politicians and occasionally to some extent by cybertroopers, include:

- Issues involving 3R (Race, Religion, Royalty).

- Underdeveloped infrastructure and need for access to basic needs and services.

- Freedom of expression and speech (avoiding misuse).

- Candidates’ position and views on LGBTQ+ matters.

- Cabinet reshuffling and efforts to topple the Federal government.

- Target on the youth-focused Malaysian United Democratic Alliance (MUDA) party.

Besides, an evidence of political computational propaganda was predominantly found on platforms like TikTok, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, including use of bots to amplify hashtags (e.g. the #13Mei incident) and spread fake news through advanced algorithms, making human-driven hoaxes distribution networks more challenging to detect as such efforts have a lower likelihood of suspension by social media platforms.

The challenge with such provocative propaganda is that once an oft-repeated false claim takes root in people’s minds, it becomes challenging to remove, further fuelling polarisation in social media. Moreover, many recipients of these narratives are unlikely to perform fact-checks due to their limited digital literacy and the lack of reliable fact-checking platforms prepared by credible stakeholders.

Increasing racist sentiments and hate speech in Malaysia’s cyberspace

Based on recent social media coverage by news agencies and commentaries, the rise of racism, ethnic stress, and propagandised narratives involving race and religion sets a substantial risk to Malaysia’s national security, social harmony, and peace.

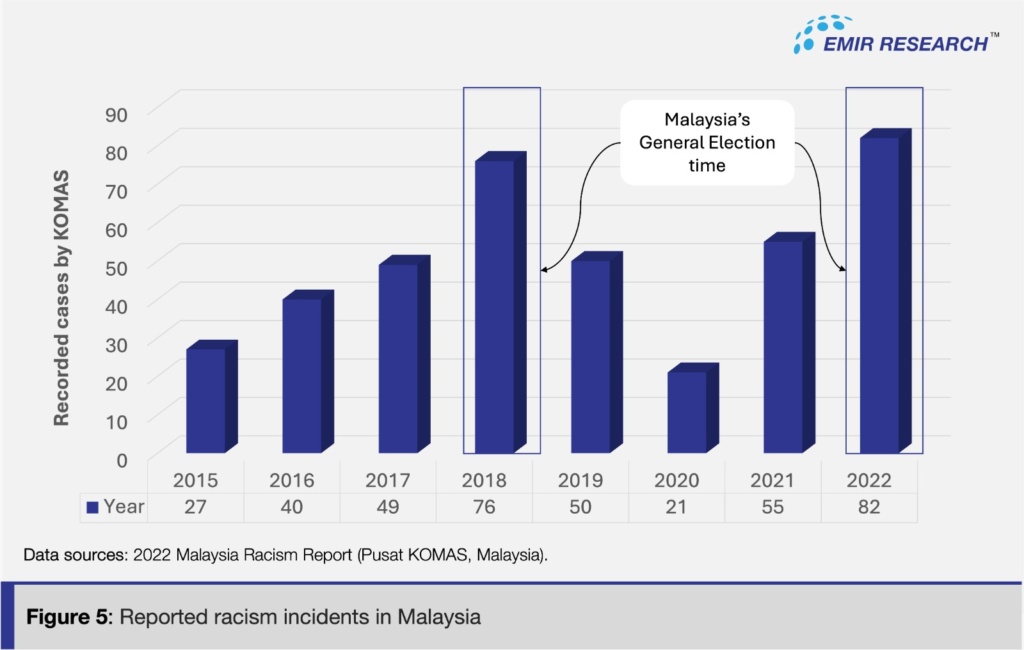

The 2022 Racism Report by Pusat Komas highlights cases of racism typically surge during general elections (2018 and 2022) (Figure 5). In 2020, though, there was a significant decrease, with only 21 cases, the lowest since 2015, probably coinciding with reduced political activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Malaysians then united via initiatives like #KitaJagaKita and #BenderaPutih, using social media to bridge racial and religious divides and criticising the incompetence of the then administration under Muhyiddin Yassin.

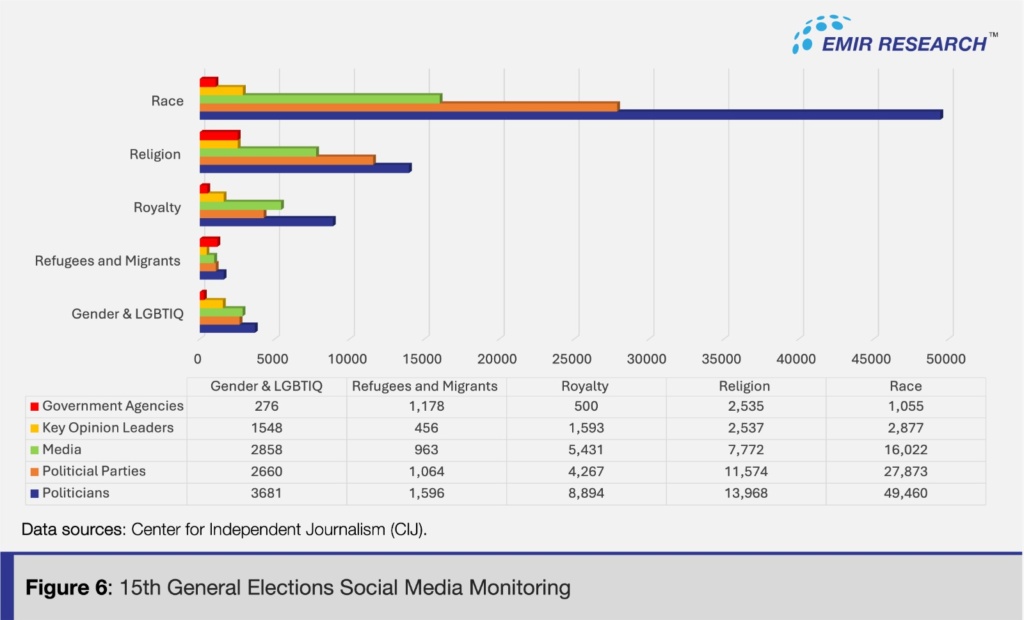

Evidently, the GE15 social media monitoring report by the Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ) revealed that discussions related to religion amounted to 38,386 mentions, while mentions concerning race reached 97,287, which garnered the most attention across various social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, and YouTube during the GE15 period. Of particular significance is the fact that politicians and political parties were prominent contributors to these discussions, accounting for a combined total of 77,333 mentions related to race and 25,542 mentions of religion in the pre- and post-GE15 timeframe (see Figure 6).

In addition, the Buddhism, Islam and Religious Pluralism in South and Southeast Asia

report by the Pew research center, a non-partisan American think tank, found that nearly seven in 10 (69%) of its’ Malaysian Muslim respondents overwhelmingly support that religious leaders should talk publicly about what politicians or political leaders they support, and 60% of these respondents say religious leaders should be politicians.

At this rate, will Malaysia ever successfully disentangle the misuse of religion from politics?

All three reports suggest a strong connection between political affiliations and identity-politics sentiments associated with the rise of the digital network. This trend, if unchecked, can lead to more division and manipulation by political leaders, with society as the ultimate loser.

To maintain fairness, politicians must face equivalent penalties for inciting misinformation, just as the public does.

With shallow, emotionally charged (as opposed to rationally argued and able to withstand critique) social media overtaking traditional campaigning, politicians hide from real issues (e.g., health disparity, food security, ageing population, access to quality education and healthcare, poverty and inequality) by stirring and manipulating feelings of the masses to gain votes while doing nothing substantial and beneficial.

Meanwhile, NGOs, oppositions, media, cybertroopers or even rakyat frequently express frustration regarding restrictions on freedom of speech and expression. Government policies often influence these limitations, leaving room for bias and limiting the open expression of thoughts and opinions.

It is essential to distinguish between freedom of speech and its boundaries when that disrupts the national peace and security of the country.

Freedom of speech in Malaysia, a democratic right, enables individuals to express opinions without censorship under Article 10 (1) of the Federal Constitution. However, when it incites violence, hatred, or threatens unity, authorities can impose penalties Article 10 (2).

Thus, finding a balance between freedom of speech and social stability is imperative. This fine line should be established through well-defined legal standards and ethical principles (which Malaysia still lacks), upholding democratic values while addressing threats to societal stability and security.

In essence, leveraging new media for political manifestos is not intrinsically harmful. It is a worldwide challenge of how politicians utilise social media.

For instance, as observed in Singapore’s 2023 presidential election, both right- and left-winged candidates campaigned using social media. However, the candidates prioritised state development over divisive rhetoric, fostering a more constructive approach, unlike Malaysian politicians who constantly use the race and religion card for their gains.

Considering the highest number of social media users are youths, the persistent spread of toxic propaganda and hate speech about racism feeds the rise of violent extremism, especially among young voters who may not fully discern false information due to low political literacy or maturity.

Paradoxically, policymakers should bridge this gap, but their actions often exacerbate the issue, making them part of the problem of responsible social media use.

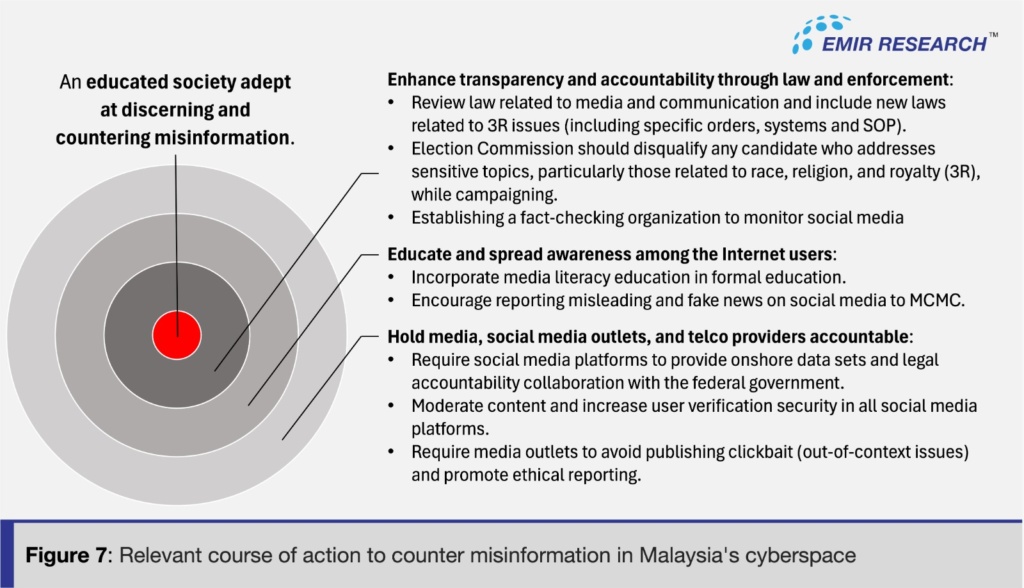

There is no turning back to further technological progress and digitalisation. However, the Malaysian government can seize various opportunities to enhance cyber-space monitoring within Malaysia. Figure 7 presents the proposed policy recommendations by EMIR Research to the relevant stakeholders.

Apart from workable policies, we, the public, should recognise that politicians will always act in their political survival interests, often disguised as serving or bringing justice to the people. Therefore, as citizens, we are responsible for exercising wisdom by seeing past empty promises and political favours offered by these figures.

Instead, we must prioritise the long-term impact of policies and future generations’ well-being before becoming keyboard warriors for political entities.

Dr Margarita Peredaryenko and Jachintha Joyce are part of the research team of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.