Published in Astro Awani, image by Astro Awani.

As Malaysia evaluates its border reopening standard operating procedures (SOPs), the first question for Malaysian policymakers is this: can our healthcare facilities cope with the higher-end projections of Omicron’s wave with current/existing border restrictions?

In other words, if the authorities are struggling with our own citizens overwhelming the healthcare facilities, then it’s logical to address this first before they think they can handle an influx of international travellers. For example, this could be addressing any issues pertaining to low vaccination uptake and/or an overwhelming infectivity rate.

Yes, it is understood that the border reopening is to balance the economy alongside public health (and a good timing for Johor politics given Johoreans’ desire for increased cross-border movements with neighbouring Singapore) but ultimately, the limiting factor to increased human interactions (inevitably, higher virus transmission) would be healthcare capacities.

Therefore, the first thing – be it for our own citizens or to prepare for border reopening – is to increase our healthcare capabilities. Whatever the final SOPs would look like, we cannot escape this primary need as there is an increase in hospital admissions and utilisation of ICU beds nationwide.

This is then followed closely (or, alongside) addressing vaccination uptake and reducing infectivity rate. Perhaps there should be a target milestone for the latter two parameters to decide the best time for border reopening.

Assuming the above are taken care of, only then we can proceed to ease restrictions. The following are key considerations in developing the SOPs:

A. Current vaccines are clearly effective at reducing disease severity, but less clear when it comes to reducing transmission.

There have been studies on the Delta variant which found that vaccine impact on reducing transmission of Delta is minimal. Omicron is more transmissible than Delta, and vaccines and boosters are still based on the same design i.e., it’s good at inducing systemic immunity, but unlikely to be as effective to induce mucosal immunity (for example, in the lining of our respiratory tracts).

Thus, it’s a reasonable conjecture to assume that current vaccines would also have a similarly minimal impact on peak viral loads, and therefore, minimal impact on transmissibility. In other words, both vaccinated or boosted could have similar levels of transmissibility.

B. That said, it is also true that vaccinated people who are infected tend to have faster viral clearance, which means that even if levels of transmissibility are similar, vaccinated people have a shorter window to do so.

People who are symptomatic (such as runny nose or sneezing) could be shedding more viral loads – i.e., a higher risk of transmitting to others.

Therefore, these first two points form the vaccination hierarchy in terms of an individual’s risk to the public.

C. Another risk hierarchy would be originating country status, as removing border restrictions exposes the country not only to increased transmission but also to other variants abroad.

Most recently is the emergence of an Omicron sub-variant (BA.2), which is reportedly 30 per cent more contagious than the “original” Omicron (BA.1).

According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) weekly epidemiological update dated February 22, BA.2 has been reported to become dominant in ten countries namely Bangladesh, Brunei, China, Denmark, Guam, India, Montenegro, Nepal, Pakistan and the Philippines.

In WHO’s subsequent report dated February 22, the relative proportion of BA.2 has increased over time and is the dominant lineage in 18 countries, whereby the report noted that “this trend is most pronounced in the South-East Asia region, followed by the Eastern Mediterranean, African, Western Pacific and European Regions”.

Whether BA.2 causes more severe disease appears to still be mixed bag and too soon to tell conclusively, but there are studies indicating a worrying trajectory i.e., potentially more severe, and could evade the immune system, including even prior BA.1 infection.

We will need more data to confirm this, but it’s best if we could avoid having the Malaysian people as guinea pigs providing the data and in the face of uncertainties, it’s best to err on the side of caution.

Thus, we cannot simply remove all restrictions and forego all SOPs, because there is still a need to reduce the rate of transmission and detect variants even if we cannot stop its circulation entirely.

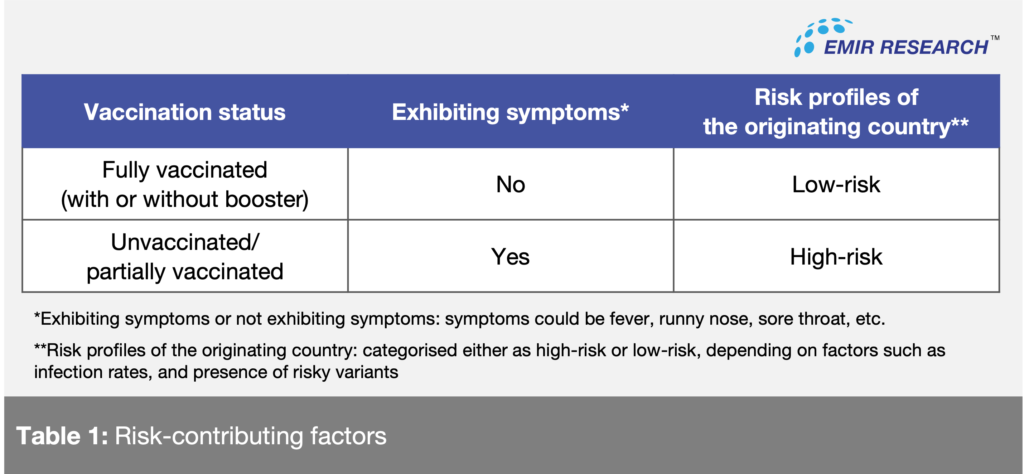

Based on the above key points of consideration, Table 1 demonstrates examples of risk profiles that differentiate between 1) vaccination status, 2) manifestation of symptoms, and 3) originating country risk profile.

Based on these examples of risk contributing factors, the authorities can create a risk profile matrix of eight general categories/hierarchies with the corresponding general SOPs for a gradual and controlled border reopening.

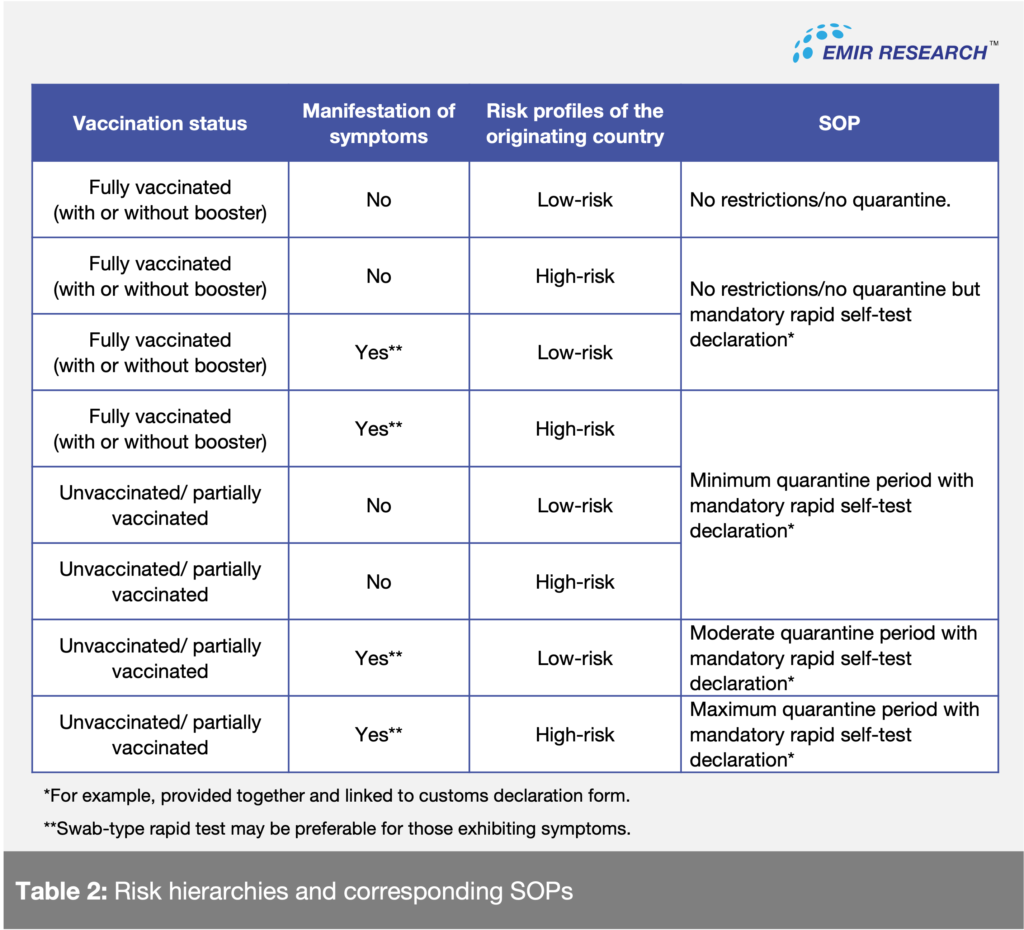

Table 2 is an example of how the authorities can respond to varying degrees of potential risks:

There are several measures that must be in place to ensure these SOPs are well-supported and effective. For example:

a. Ensuring quality control and correct use of rapid self-test kits

There must be a ramp up on quality control of self-test kits given its mass production and emergence of variants. There are accuracy concerns regarding these test kits which the entire strategy hinges on.

Some people don’t know how to use self-test kits properly, and circumstances could affect the results of the rapid test. There must be in-flight instructions and/or at the airport/ground border control stations on how to use self-test kits properly.

Since swab-type rapid tests may be more accurate than saliva-based, these should be used for people manifesting symptoms and/or coming from high-risk originating countries. For this, Authorities have to allocate trained staff to handle the swab sampling.

b. Create a “MySejahtera” application (app) for non-Malaysians entering the border with compulsory contact tracing

As proposed in a previous EMIR Research article (Navigating the Omicron Wave, February 11), in addition to alerting app users of historical close-contacts, the MySJ Trace feature of MySejahtera should be tied to early warning and prevention system so that people can avoid high-risk places in the first place.

This empowers people to make better choices for themselves and alleviate public health burdens. Historical back-tracing for a highly transmissible variant in a community with a high-infectivity rate would be tedious and ineffective.

A mandatory “Check-in” on the app should be enforced to declare health status every day or every other day, depending on the originating country’s risk profile. Failure to do so may be tied to the validity of travel visa or other relevant documents, penalties, and movement restrictions when entering premises (e.g., QR code scan rejection).

c. Ramp-up randomised swab tests and genomic screening

Variants such as BA.2 are known as “stealth” Omicron as PCR may not distinguish it against other Omicron sub-variants, and it won’t be the last variant with such characteristics. The trade-off for reduced restrictions when opening borders would be increased in random swab tests and genomic screening. It would be reasonable to allocate a higher frequency of random tests among higher-risk groups as per the risk profile matrix.

On this note, authorities must ensure PCR kits (and methods) are up-to-date to detect new and emerging variants and ensure larger laboratory capacities to handle higher sequencing volumes. Sequencing is the only definitive way for variant confirmation.

The above are examples of general recommendations. Malaysia may formulate special considerations with neighbouring countries such as Singapore and Thailand (or other countries for diplomatic reciprocity) due to economic reasons and the high frequency of land border crossings.

Special considerations may include the number of people, visas and permits, travel bubble mechanisms, and health insurance.

In summary, border reopening considerations must first be based on our ability to control its impact on public health, and should include proper and thorough execution of strategies outlined in the framework.

The proposed SOPs should minimise the rate of transmission and increase vigilance on the risk from variants, while being nimble and flexible in making necessary changes to balance economic and diplomatic needs.

Ameen Kamal is the Head of Science & Technology at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.