Published by SinarDAILY, BusinessToday, Astro Awani, Asia News Today & Focus Malaysia, image by SinarDAILY.

Despite the broadest publicity, all sort of advocacy and lobbying by various interested parties involved, the so-called single wholesale network (SWN) model proposition by Digital National Berhad (DNB), as it stands today, doesn’t hold water from the perspectives of nation-building, technical feasibility, financial and commercial viability as well as governance and integrity.

Therefore, this matter deserves urgent and closest attention, the highest level of scrutiny, radical transparency, and open and extensive public debate. Writing wide-page advertorial content that, in fact, raises even more critical questions and self-contradictions than providing definitive answers is one thing. However, it takes a whole new level of viability, economic sense, and feasibility to withstand open and live public debate with experts from across the industries.

In this series of articles (2 parts), EMIR Research invites the public and policymakers to critically relook into all the publicly available information surrounding DNB-led SWN proposal that transpires so far from those same critical angles—technical feasibility; financial and commercial viability; governance and integrity and of course widely-claimed intergenerational impact on the national wellbeing.

The first part focused on the technical feasibility and financial viability.

This article will discuss the issue of governance and integrity as well as the impact on nation-building in the following manner.

Governance and integrity

Firstly, in looking at Singapore’s 5G governance ecosystem, our neighbour doesn’t rely only on Ericsson. While as one of the telcos awarded with the operator license by the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), Singtel Ltd is using Ericsson also, the other two, i.e., the M1-Starhub joint-venture (JV), have opted for Nokia for the 5G standalone architecture. Hence, there is no network equipment provider (NEP) monopoly as in the case under the SWN model in Malaysia.

What this simply means is that Singapore’s 5G governance (institutional framework) is business model-friendly – as the different telcos can synergise and link up with a specific NEP tailored to their market strategy and customer base.

To quote from Starhub:

“StarHub can create several secure mobile campus networks for localised functions through network slicing capability. The operator can also leverage mobile edge computing services to host AI-based solutions such as facial recognition services and to deploy advanced IoT solutions” (“Nokia and StarHub partner to expedite standalone 5G services for Singapore customers”, Nokia).

On the argument that “DNB will be properly governed due to the existence of Board of Directors”, this is superficial reasoning or logic. Learning from the 1MDB scandal, financial oversight and prudence will be crucial for DNB. Relying on internal governance and code of business conduct subject to the oversight of the Board of Directors will not suffice. This is especially pertinent when the Prime Minister or Finance Minister (who can be the one and same person) holds the governance “trump card” and has the ultimate say.

Independent mechanisms on the appointment of Directors and full transparency of data accessible to properly empowered independent oversight entities will be required to prevent financial abuse and misappropriations.

As to the issue involving rural coverage, this can readily be deployed via the pre-existing Universal Service Provision (USP) fund. The USP fund has been in existence since 2002 under the oversight of the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), where licensees have to contribute 6% of weighted net revenue every year.

According to The Edge, “[b]etween 2003 and 2020, annual contributions ranged from RM512.1 million in 2004 to RM1.98 billion in 2018, averaging RM 1.18 billion. As at end-2020, the USP fund had RM10.09 billion in accumulated funds, money that is already being earmarked to bridge the country’s digital divide under the Jendela initiative”.

The MCMC has allocated RM3.2 billion under the Universal Services Provision (USP) Fund for 2021 to improve the quality of broadband services with a focus on rural areas. Hence, there’s still considerable massive financial “firepower” left – which can be deployed to ensure all the rural areas (both in West and East Malaysia) can be covered – with fibre – to the fullest extent possible.

In fact, since such impressive funds have been readily available for the development of internet infrastructure in the rural areas since 2003, it is probably worth thoroughly investigating why until now there is no impact and whether all funds are there?

As for DNB venture financing, the much-vaunted grandiloquence about the “securitised future cash flows” which gives the impression that financing will be self-sustained by income doesn’t alter the fact that DNB is still raising bonds in the form of sukuk. In other words, DNB will still be in debt (when the sukuk term matures). This means that if cash flows falter, this impacts DNB’s capability to repay the debt — which in principle is no different from the experience of 1MDB.

Furthermore, DNB promises to bridge the national digital divide between urban and rural areas via 5G coverage to expedite the catalysing of digital transformation in the country under — and this is critical — a supply-driven approach. This, of course, is the opposite of the demand-led approach of the telcos’ business model.

Whilst broadband, in general, is a utility and ought to be considered a constitutional right, and therefore should be treated as no different than other utilities (and natural resources), it’s a misconception to apply the supply-driven model.

The supply-driven model undertaken in many states with respect to the provision of treated water is to be differentiated from 5G. Unlike treated water which knows no other category, 5G is a specific type of cellular technology within the broad concept of broadband—likewise 4G and so on. The provision of fibre, including fibre to the home (FTTH) for fixed broadband and mobile broadband, is sufficient to satisfy the purpose of a supply-driven model (as a typical utility like treated water and electricity) without the need for 5G coverage as such.

Notably, according to the National 5G Task Force Report: 5G Key Challenges and 5G Nationwide Implementation Plan (2019):

“In terms of pace, 5G rollout will be similar to 4G: slow for the first 1-2 years but will accelerate once cheaper and more affordable 5G devices come to market in 3-4 years. However, 5G will be more difficult to implement because:

- Cost of 5G radio is expected to be 4-5 times more expensive compared to 4G.

- 4G ecosystem will still be dominant in the next 4-5 years, meaning network investments will still be focussed on improving 4G.

- 4G was quicker to scale and roll out” (p. 50).

DNB’s much-touted claim that the SWN model will enhance a speedy 5G rollout contradicts (the findings of) the Report.

Moreover, even Singapore, which is only the size of one fifty thousandth of Malaysia, is projecting a full island-wide coverage by only 2025 in the context that not all of the Malaysian landmass is populated.

DNB’s plan is for 5G deployment to reach approximately 39%-40%% coverage by the end of 2022 and 73% in the following year and 86% by 2024.

Is DNB’s aim realistic in any way?

It is interesting that despite obvious telco business disadvantages of multi-operator core network (MOCN) model as discussed in “Deconstructing 5G Rollout in Malaysia — Part 1” there have been talks of telcos proposing Dual Wholesale Network (DWN) model where they could form the alternative consortiums

At least DWN could complement and supplement the speed of the 5G rollout – but based on a demand-driven business model. And not least, more in line with the thinking and recommendations of the Report. To quote from the Report again: “Active sharing in the form of… MOCN [multi-operator core network], antenna sharing, etc. can be mixed among telcos. However, all of these methods should be carefully evaluated to ensure no impact on quality”.

Another consortium would provide telcos with the flexibility needed for their respective business models – whether based on MOCN or not.

Having two consortia would also spur competition in quality and standards, and ensure checks and balances between them.

DNB is yet to prove to be the solution to the national internet problems and more

DNB promises to deliver wider (bridging national digital divide) 5G coverage faster to simply “catalyze digital transformation in Malaysia”.

The following word-to-word quote from TheEdge reads rather classic, in the context of current Malaysia governance and policymaking style: “The rollout by DNB is already underway. The commercial launch was on December 15, 2021. The target population coverage is to reach 39% by the end-2022, 73% in the following year and 86% by 2024. Clearly, the argument of slower rollout by DNB is wrong—based on the company’s target coverage schedule above.” And full stop there, no data or research such as, for example, at least a simple needs analysis to support such ambitious targets.

This is because our policymakers, conveniently, in their haphazard planning, never try to understand and back by data and research the causal relationship between the planned inputs-outputs and expected outcomes-impacts.

Before quoting Korea as an example and benchmark for 5G adoption, we must acknowledge that countries like China, Korea, Singapore have spent at least the last three decades meticulously, rationally, consistently building up the foundational blocks for the 4th Industrial Revolution (4IR) while our country has spent the same decades on largely procrastinating and destroying those foundations. Therefore, for these countries, 5G is a necessity and super quick in uptake as 4IR progress is already ubiquitous in their populations.

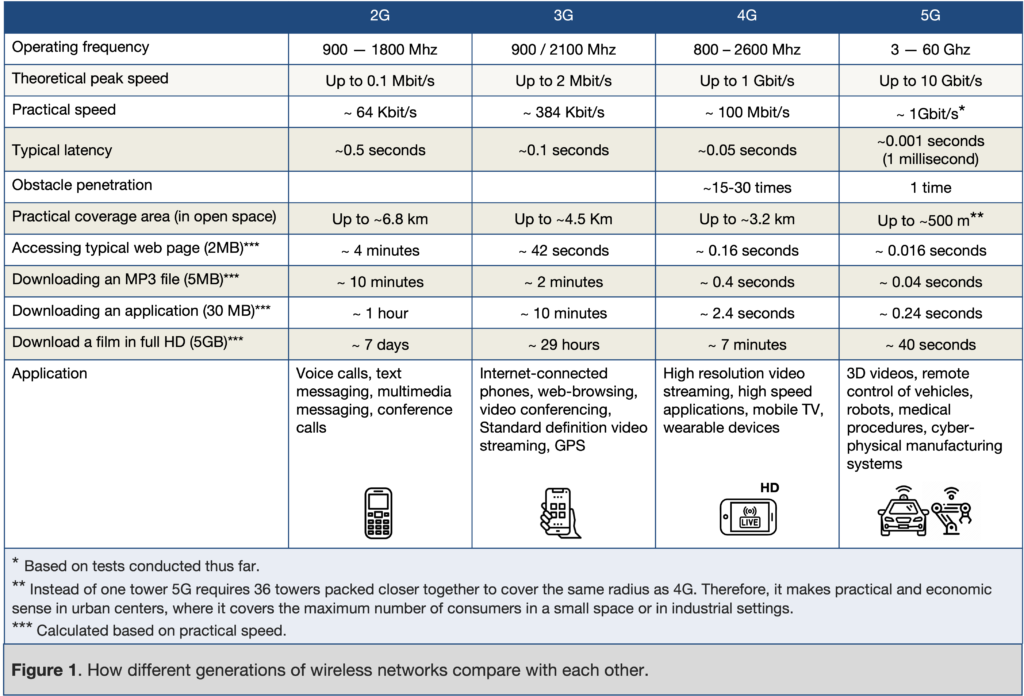

The Dotcom bubble has taught the world that IT solutions are very much demand- and needs-driven! The following figure helps us understand better where 5G stands in terms of needs and compatibility with other techs.

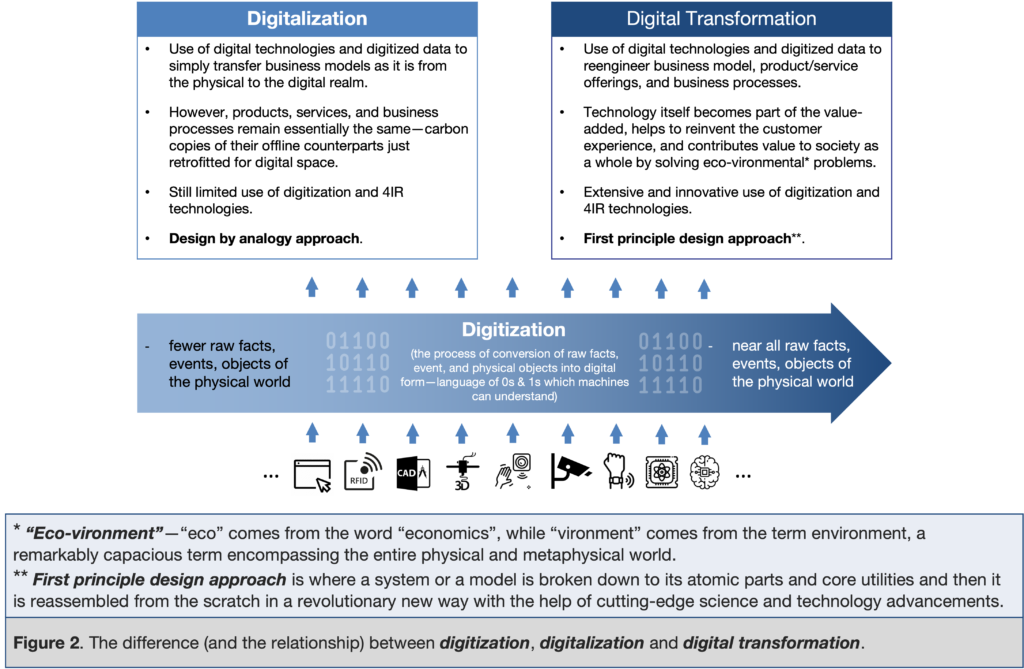

When we look at the current state of our nation and how we are lagging even in basic digitalization (forget about digital transformation as it is a whole new level — see Figure 2), we understand that the 5G requirement will be extremely patchy in our country and driven mainly by individual enterprise solutions at least for another few years to come.

Therefore, there is no urgency in pushing 5G population-wide. However, there is incredible urgency of yesterday to streamline all our national policies aimed at nurturing (through education system) well-rounded citizens who are well-positioned and empowered to face, navigate, and thrive 4IR, championing deep integration of 4IR frontier technologies at every level of society (individual, industry, government, and environment) streamlining all inefficiencies and corruption and encourage growth and progress for all. And in doing so, we need to maximize the impact per every dime spent—we have absolutely no more room for white elephant projects.

For example, until now, the government has done absolutely nothing to change our schools and tertiary curriculum. We have severe skills mismatch even during the 4G era—most of the fresh graduates do not have the necessary tech/digital skills as these skills are now required across all industries. We are not producing digital creators but digital consumers, and until this changes, 5G will not add any value to our economy.

The internet usage data can be a gross indicator of where Malaysia is as a value-added “adopter”. For example, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) recently reported that 81.2% of Malaysians use the internet to mainly download media and play games (indicating a strong focus on entertainment), while an embarrassingly small percentage engage in productive activities such as professional networking (9.1%), content creation (11.8%) and learning from formal online courses (4.8%). And this is merely with internet penetration of nearly 90% of the population!

Therefore, increasing speed or bandwidth through 5G does not necessarily mean more productive use of the technology. Mentioning South Korean’s ability to watch a live baseball game from various angles and the use of Augmented Reality does not seem to add much value to Malaysia’s economy. Not to mention that not many people, especially in the rural areas, will not readily have access to gadgets that can utilise 5G — unlike basic internet connection. So what demand DNB is talking about is not clear.

Thus, 5G that is not complemented with high added-value, innovative use that generates real productivity will not enable “moving out of the middle income” trap. These projected “sophisticated activities” that can be done faster and better must be identified and expanded upon.

Even if 5G manages to boost the economy as claimed, becoming a “high income” nation has been an old moving target. Comparisons with other high-income nations such as Singapore or South Korea are meaningless given Malaysia’s apparent level of governance and inequitable economic practices that widen the wealth disparity, running contrary to the widely touted “shared prosperity” illusion. The question with “high income” is always: high income for who?

Now let’s look again at the needs for 5G (Figure 1) and our rural areas in that unfortunate and undeserving condition as they are now. Clearly, right now, they need 5G like a fish needs a bicycle.

For decades, our rural areas have been screaming for better basic infrastructure in terms of everything, not just internet basic infrastructure. You are talking about bringing smart healthcare there via 5G while the rural dwellers, if they have the right to choose what to do with the same amount of money, would rather ask: “Please bring and significantly improve at least basic healthcare infrastructure here. Bring economic activities here! Make rural areas attractive places to live again!”

You want to quote Korea, Japan? They are uplifting construction infrastructure and living standards in rural areas! They bring youth (as young as in their primary school years) back to rural areas to make them interested in smart farming and thus solve country’s food security issue, which is, by the way, more pressing for Malaysia than for these countries, as the Global Food Security Index indicates for more than a decade. And for smart farming for example, even reliable 3G connection will suffice but financing and a connected ecosystem are direly needed.

All in all, we need to start seeing and applying solutions where they are needed and when they are needed. But this has been the government approach for quite some time: instead of gradually investing in the serious renovation of the house structure, we are not even patching the cracks on the wall—we put beautiful pictures to cover them until the whole house collapses (ringgit-spinning with no impact).

As we can see, the DNB proposition debate is a complex issue with numerous far-reaching implications for our economy and national future. Such fateful decision making cannot happen behind closed doors.

It requires full transparency of all relevant data (pertaining to ALL relevant costs and benefits) to verify and substantiate technical, economic and financial assumptions and necessitates systems thinking approaches brought to light in a live public debate. The outcome must be a synergistic win-win arrangement with respect to the cost-benefit for all stakeholders.

Rais Hussin, Margarita Peredaryenko and Jason Loh are part of the research team of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.