Published by AstroAwani, MYsinchew, AsiaNewsToday & NewsHubAsia, image by AstroAwani.

Malaysia’s newly-elected unity government has placed lowering the cost of living as one of its main priorities, which, among other things, implies the dire necessity to focus on urgently strengthening national food security. After all, the food items have been topping the list eating up the monthly budget of the B60 category recently.

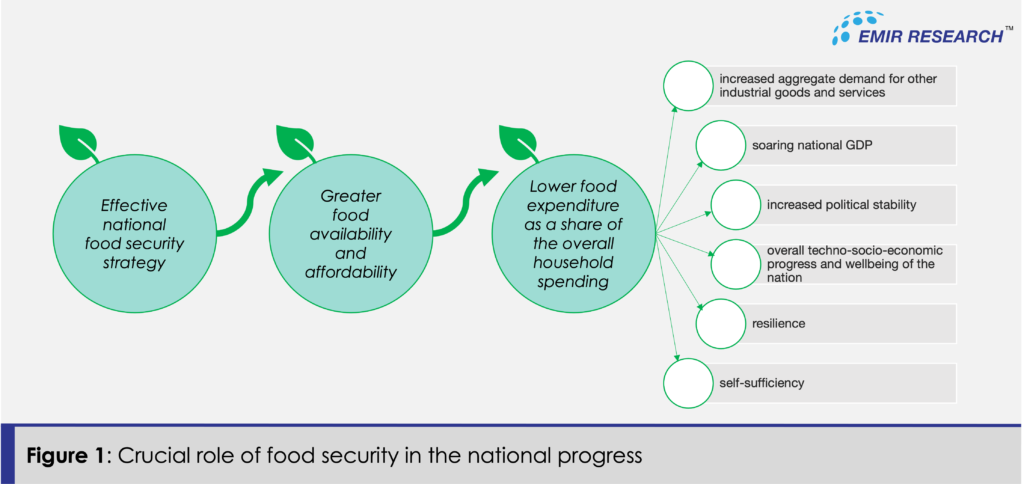

Furthermore, the sphere of national food security is an invaluable pillar of the overall national development strategy via its reciprocal link to other spheres of socio-economy (Figure 1) with far-reaching implications such as increased aggregate demand for other industrial goods and services, soaring national GDP, increased political stability and overall techno-socio-economic progress and wellbeing of the nation.

Aligning strategic framework with the global trends

Earlier EMIR Research has argued that a solid national food security strategic framework must be aligned with the global food security trends (Figure 2) that are discerned by examining the experience of countries leading global food security forefront (for more details, refer to “4IR Towards National Food Security: Alignment with National Agrofood policy 2.0”).

In this article, in two parts, EMIR Research proposes an alternative radical, holistic and strategic framework for national food security, congruent with the global food security trends as an outcome of its continuous focus and research in food security since 2019.

The vision, mission

The proposed strategic food security framework is anchored to one Vision achievable through spearheading nationwide efforts in the four key strategic directions or goals.

The vision aspires to make Malaysia “completely self-sufficient, at least in its core staple food items”, making it more resilient to global supply chain disruptions, be it due to future pandemics or threatening geopolitical situations.

Although ultimate self-sufficiency, also known as food sovereignty, is an ambitious target for Malaysia, given the dismaying state of its current national food security. However, as a rightful domain of national security, Malaysians cannot be deprived of staple food items under any external circumstances. Furthermore, since spearheading national efforts towards self-sufficiency in food production is the key trend globally and regionally, the opportunities for import may shrink further soon.

To achieve this envisioned state, the mission intends to “implement sustainable models based on global food security strategy trends to pool unutilised and underutilised resources in financial, land, manpower and talents, and technology to pursue the strengthening and resilience of local food supply chains”.

Goal 1—Uplifting the status of food security

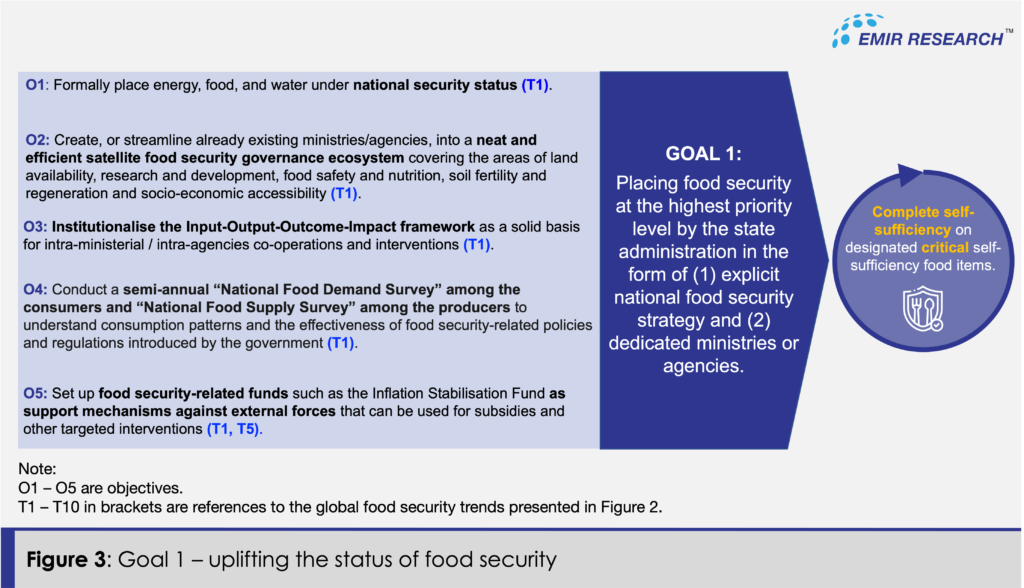

Uplifting the status of food security means placing food security at the highest priority level by the state administration in the form of (1) an explicit national food security strategy and (2) dedicated ministries or agencies.

The following objectives are suggested to propel the movement in this strategic direction (Figure 3).

Objective 1: Formally place energy, food and water under national security status.

The global food security experience reveals the future of food security is inextricably connected with tech (and therefore renewable energy) and national water resources. As such, these three elements, energy, food and water, are warranted to be placed under the umbrella of national security.

Objective 2: Create, or streamline already existing ministries/agencies into a neat and efficient satellite food security governance ecosystem covering the areas of land availability, research and development, food safety and nutrition.

Objective 3: Institutionalise the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact framework as a solid basis for intra-ministerial / intra-agencies co-operations and interventions.

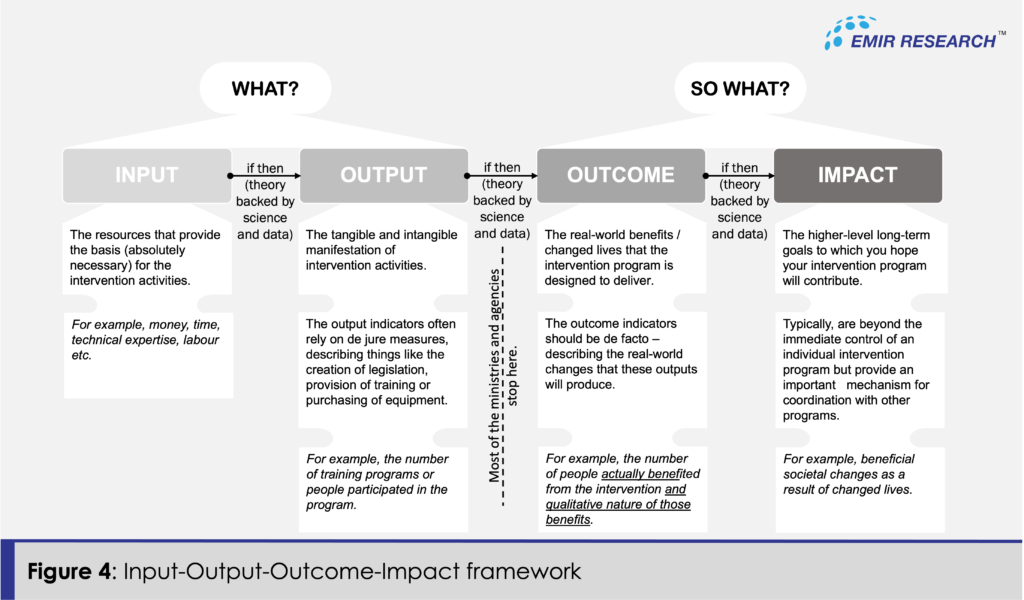

The Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) framework is logical and robust reasoning (solely based on science and data) of the entire causal path from inputs (scarce resources/capitals) to outputs (tangible and intangible manifestation of intervention activities) to outcomes (real-world benefits/changed lives) and finally to impacts (higher-level intergenerational goals, if we speak in the context of a nation) (Figure 4). Importantly, each level comes with a set of metrics to track the progress of transforming inputs into outcomes and impacts. The science- and data-backed logical links between inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts also clearly guide interministerial and interagency cooperation based on real need and opportunity to make an impact.

Objective 4: Conduct a semi-annual “National Food Demand Survey” among the consumers and a “National Food Supply Survey” among the producers to understand consumption patterns and the effectiveness of food security-related policies and regulations introduced by the government.

These surveys are important data sources to evaluate the effectiveness of implementing this proposed strategic food security framework. The key performing indicators can be devised and regularly measured in the nationwide surveys (from producers’ and consumers’ perspectives) to track the progress in moving along all four goals proposed under this strategic framework and possible corrective measures underpinned by the IOOI model to strengthen the foundations of all food security related functions.

Objective 5: Set up food security-related funds, such as the Inflation Stabilisation Fund as support mechanisms against external forces that can be used for subsidies and other targeted interventions.

Goal 2 — Towards self-sufficiency

An overreliance on imports, especially in food, is a matter of national security. Furthermore, the recent fusion of 4IR technologies with the agriculture sector renders such terms as “comparative advantage” and “economies of scale” obsolete. It is also worth reminding again that moving towards self-sufficiency in food is the trend among other nations. The nations are increasingly turning towards serving and prioritising their local food markets, which gives yet another impetus for being proactive in this direction.

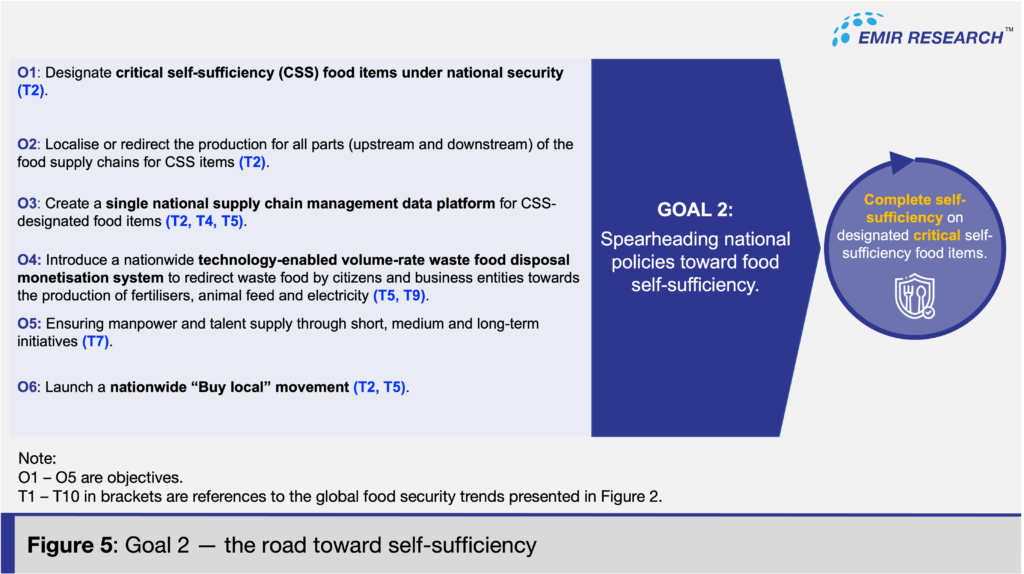

Therefore under goal 2, EMIR Research proposes to focus the efforts on “Spearheading national policies towards food self-sufficiency”.

The following objectives are suggested to propel the movement in this strategic direction (Figure 5).

Objective 1: Designate critical self-sufficiency (CSS) food items under national security.

Given limited resources, selected food items should be initially put under the critical self-sufficiency initiative (CSS) based on nutritional value for human health and considering the composition of staple food ingredients across the different ethnic groups comprising Malaysia’s population.

Objective 2: Localise or redirect the production for all parts (upstream and downstream) of the food supply chains for CSS items.

External market forces and supply chains can impose shortages and/or higher prices on local supply chains. Therefore, an overreliance on imports, directly for the food or importation of the inputs to its local production, is a matter of national security. Therefore, all parts/inputs of the CSS-categorised food supply chain have to be localised to ensure the availability of supply and management of costs.

Objective 3: Create a single national supply chain data management platform for CSS-designated food items.

All the suppliers of raw inputs, food producers, distributors and retailers for CSS-categorised food must be onboarded on this platform. However, the platform can expand beyond CSS-categorised items.

This supply chain management platform must be established under national security provisions. Under such a provision, the supply chain may function according to market forces under normal circumstances, but subject to events that would qualify as a crisis or an emergency, the dedicated supply chain network under the national food security ecosystem would commit to playing special national security functions.

For example, players in the supply chain would commit to transparency and mutually agree for costs and prices to be governed and controlled to shorten the supply chain and minimise transfer prices to ensure the survivability of industry players whilst minimising price impact to end consumers.

Objective 4: Introduce a nationwide technology-enabled volume-rate waste food disposal monetisation system to redirect waste food by citizens and business entities towards producing fertilisers, animal feed and electricity.

The experience of other countries already demonstrates how much value can be unlocked through reducing food waste and loss. For example, collected and processed food waste can create the most organic and soil-replenishing fertilisers, probiotic feed to strengthen the immune system of livestock, and even alternative forms of electricity. At the same time, the maintenance of such an elaborate, infused with technologies and science ecosystem for food waste and loss management can create thousands of new skilled job opportunities for Malaysians.

Furthermore, reducing or eliminating food waste and loss in landfills is synonymous with potent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This is because the methane gas generated by the rotting food waste in landfills has dozens of times more negative impact on our atmosphere than even CO2. Therefore careful food waste and loss management can significantly fast-track Malaysia’s progress towards achieving a net-zero GHG emissions target by 2050.

Objective 5: Ensuring manpower and talent supply through short, medium and long-term initiatives.

Immediate measures may include using foreign labour and experts, though this must gradually shift towards using local talents.

The short-term strategies must include boosting upskilling and reskilling efforts. Courses may include modern farm management, urban farming, soil fertility and regeneration, alternative or natural fertiliser and soil conditioning, various agritech tools, and marketing and supply chain management. The focus should be on the existing workforce in agriculture, plantation, and animal husbandry.

Medium-term strategies involve the exposure of tertiary education students to the activities from the short-term measures mentioned above through incorporating a mix-and-match academic culture whereby students from one discipline can minor in or adopt a discipline or field of study from a different faculty.

Longer-term efforts involve exposure at primary and secondary levels, whereby researchers in the field and tertiary students in the relevant courses set up pilot/demonstration projects at school premises as part of their course requirements. The objective is to expose agritech, farming and animal husbandry early on as a field that is high-tech and lucrative while teaching fundamental concepts.

Objective 6: Launch a nationwide “buy local” movement.

Aligning the individual consumers’ behaviours with the overall food security strategy shall not be the last in terms of its importance. The countries that spearhead their efforts towards food self-sufficiency through a significant boost of local production quickly realise the power and absolute necessity of consumers’ support towards prioritising local producers.

This warrants creating a single “locally produced” label and its active promotion in various awareness campaigns.

Part 2 of this article shall focus on how Malaysia can build vibrant ecosystems around food security (Goal 3) and the energy-food-water nexus (Goal 4).

Dr Rais Hussin is the President and Chief Executive Officer of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.