Published by Astro Awani, MYsinchew & BUSINESSTODAY, image by Astro Awani.

After nearly a year of relentless persuasion of the previous government to urgently review and revise the plan for national 5G network rollout via the highly controversial Single Wholesale Network (SWN) model under the government-owned entity Digital Nasional Berhad (DNB), EMIR Research indeed welcomes the move by the new government to investigate the matter thoroughly.

Such an initiative also aligns with the foremost priority tasks of fostering economic development synonymous with a resilient national digital ecosystem and enhancing the overall governance system.

To remind, EMIR Research, alongside the renowned local and international experts, from the very beginning, has continuously brought into question the plausibility of DNB vehicle from the perspectives of nation-building, technical feasibility, financial and commercial viability, as well as governance and integrity (for example, refer to “Deconstructing 5G Rollout in Malaysia” in two parts or “Malaysian 5G Rollout ‘Unanswerable’ Questions” for the most comprehensive review).

In summary, in its series of writings on a questionable DNB-led 5G rollout EMIR Research continuously argumentatively emphasised: 1) the critical connectivity challenges that Malaysia faces, 2) a simple solution to it, and 3) how DNB not only does not address the key problem but creates a host of new problems, including that of governance.

Key connectivity challenges that Malaysia faces

- Digital divide — lack of internet connection in rural areas. This problem is due to the scarcity or even complete absence of passive network infrastructure extended to the rural areas (fibre cables, towers and backhaul). Extension of the passive network infrastructure constitutes one of the greatest costs to Mobile Network Operators (MNOs). Given lower demand in rural areas, MNOs are not motivated to spend that much on this extension.

- Low quality of even previous generation networks (basically 4G as 3G is already near retired completely) nationwide.

- Malaysia is missing out on 4IR where 4IR is all about the proliferation of cyber-physical systems or systems that aggregate data about every object and event of the physical world, analyse patterns in it and produce a solution that can now be applied back to the physical world very often without human intervention by robotics powered by Artificial Intelligence. Malaysia also continues to lose consistently (year-on-year) critical digital skills and ecosystem.

The solution to Malaysia’s internet wounds

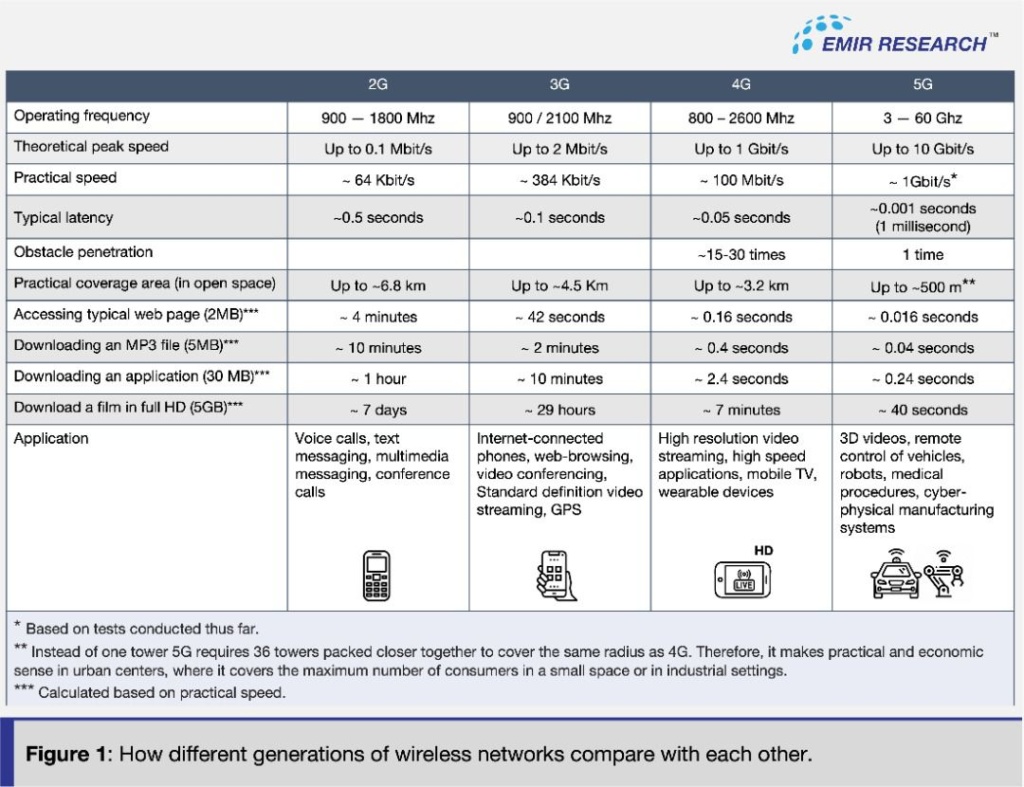

- Restructure DNB into a neutral government-owned entity that will solely focus on actively expanding passive network infrastructure, such as fibre, backhaul and towers/poles, nationwide, while prioritising the rural areas. This will enable better 4G coverage which is more than sufficient for the needs of rural citizens (see Figure 1) with, perhaps, some very patchy 5G industrial implementation based on needs analysis and specific use cases.

Keep in mind that the 5G technology proposition is for an extremely high density of connected devices, which even the most 5G successful countries, such as South Korea, found to be extremely difficult to monetise even in densely populated areas (refer “DNB’s 5G: Eternally Revolving Deadline”).

Note that this neutral and government-controlled entity can initially focus on extending passive network infrastructure to new areas but, if need be, acquire the existing passive network infrastructure, which is already built and belongs to various telecom players on a willing buyer/willing seller basis. In addition, the government can also focus on implementing policies to encourage sharing of the existing passive network infrastructure, a worldwide trend in the telecom industry.

Importantly, the Universal Service Provider fund should be sufficient for this purpose!

2. At the same time, the spectrum should be licensed to individual MNOs in a fair beauty contest, as this is precisely what other countries that have already rolled out 5G did (you can refer to an insightful study of the top 60 telecoms markets worldwide by The Economist Intelligence Unit). Note that even countries that initially faced a problem of 5G spectrum band scarcity (and therefore were considering sharing the spectrum) eventually rushed to do spectrum conversion (freeing up the suitable 5G band) just to be able to distribute it via auction or beauty contest among the MNOs.

This apparent aversion to spectrum sharing that we notice in the global 5G rollout experience is critical!

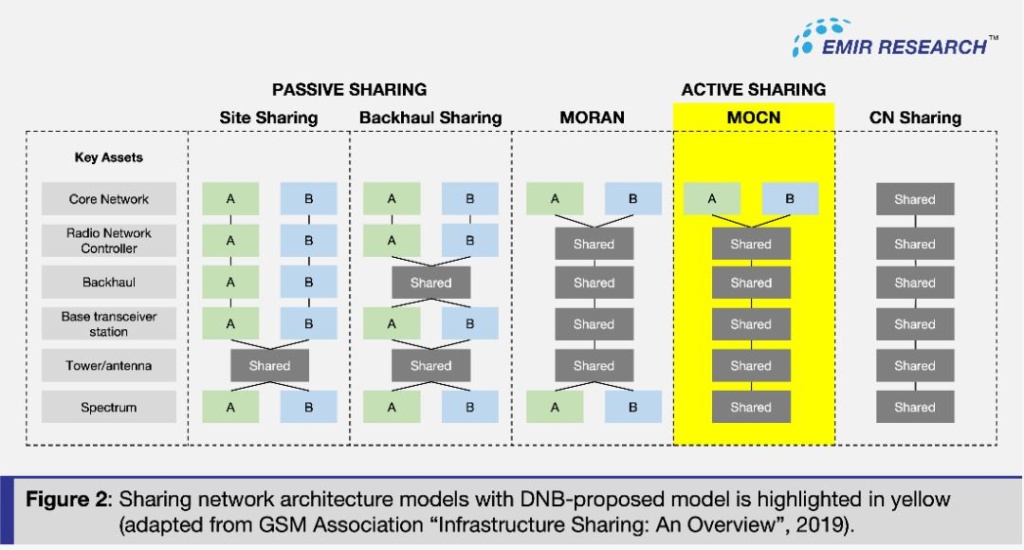

This is because the moment spectrum is shared, automatically, the active network equipment must be shared too (see Figure 2)—SWN. So, essentially, the network becomes the same, but it can be government-owned (like DNB) or belong to a consortium of MNOs.

However, when active network equipment is shared among the MNOs, we have a big problem — MNOs can no longer compete on the quality of the network, which is the key differentiating feature, while all other features, including differentiation “on retail end” which DNB keeps emphasising, are only secondary to and dependent on the network quality. So even though under SWN, MNOs may continue to own their own set of core network equipment, no matter how superior equipment they have at the core network level, it can do very little if the active network equipment provides substandard quality and some more if it is entirely out of individual MNO’s control like it is going to be under DNB. This is the critical problem! So the end result will be an industry with low competition, innovation and, as a result, low quality and no reduction in price (more on this argument in “EMIR Research response to DNB’s 5G voyage of semantics acrobatics”).

3. Strengthen the telecom license regulation. MNOs should be tightly held to a clear set of Key Performing Indicators (KPIs) in terms of the minimum required network quality and revocation of the spectrum license in case of falling short of those KPIs or incentives in case of significantly exceeding the KPIs.

4. Focus and give full-speed priority to all other initiatives that could stop the brain drain of critical technology-related skills and talents and strengthen our digital ecosystem. For example, to boost economic growth, we should focus on such areas as cyber-physical manufacturing systems and remote control systems / autonomous vehicles / robots, as these are the ones that help to monetise 5G significantly! Look at our neighbour, Indonesia, striving to become a regional hub for the electric vehicle industry. We need to look in the same direction.

What the above solution will do:

- Keep the competition in the telecom industry based on network quality alive.

- It will not delink, like SWN does, the network ownership and service delivery. And 5G, due to the specificity of its use cases, especially for enterprise solutions (the most critical segment for Industry 4.0), will require even closer cooperation between network and end-user devices than 4G.

- Sufficiently disrupt the status quo in the telecom industry to encourage even more competition based on the network quality and possibly even entry of new MNOs into the telecom industry.

- If the government can cover the cost of passive network infrastructure expansion into rural areas, MNOs could bring their 4G services much faster. If the government’s objective is to expand connectivity into rural areas as quickly as possible at the lower cost possible, then is it not better to do so with the 4G first—the technology that is already well-known and costs of deployment could be significantly lower?

How DNB does not solve the core problem but creates a host of other problems

- First and foremost, SWN or DWN models will have an inimical impact on our telecom industry, undermining competition and innovation in terms of network quality which is the paramount feature. The experience of all the countries that tried 4G SWN clearly supports this notion. However, 5G (unlike 4G) is more crucial for industry 4.0 than consumers; therefore, a quality flop for our 5G is unacceptable and devastating.

- Importantly, DNB completely ignores the key problem of Malaysia’s passive network infrastructure lack in rural areas in their proposition, especially fibre and backhaul, because it subcontracts everything to third parties and owns nothing and does nothing except project management (churning out the contracts) — one big red flag. Note that even TM does not provide “fibre leasing” to DNB. Instead, it provides bandwidth leasing – based on Gbps (not km of fibre). So now the question is who would lay the fibre and backhaul to go to rural areas, and how will it be reflected in the costs and prices of DNB and MNOs? Not clear! As well as, it is not clear how DNB is going to solve the digital divide without this clarity.

- DNB’s costs are highly-likely to be understated (and therefore, its beneficial effect is overrated) due to possible hidden costs that were either not laid out transparently or not considered thoughtfully.

For example, the proposed 10,000 towers would certainly not be enough to provide projected coverage targets by DNB (90% coverage in populated areas by 2027).

How about the cost of the aforementioned fibre and backhaul for rural areas coverage?

It is also unclear how having multiple local repeaters to access 5G signals (such as in people’s homes or in office buildings) will impact the cost to end-consumers.

In the IT world (telecom is not an exception), costs come down quickly due to rapid innovation. Therefore, it is crucial to have many players working in parallel on the research and development of active network equipment as they gradually roll out the network. Being locked with one supplier of such equipment reduces the potential for competitive and dynamic cost reduction over time. Therefore, DNB’s purported overall network rollout cost-reduction benefits might be easily overestimated and hugely overrated due to various other adverse impacts on the telecom industry as a whole and consumers, which DNB have not addressed.

- RM4 billion as estimated corporate costs over ten years for an entity that nearly owns nothing, does nothing except playing a role of a middleman of a kind, simply suggests itself for more scrutiny and breakdown.

- DNB has a highly vulnerable governance structure. DNB is government-led, with a government-linked ecosystem and beneficiaries. There must be independent monitoring (financial, technical etc.) and oversight, given that project costs include sums (reportedly an estimated RM 1 billion) allocated for Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), the body regulating DNB, and Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB). TNB’s biggest shareholder is Khazanah Nasional Berhad, owned by the Ministry of Finance Incorporated, while the Ministry of Finance wholly owns DNB. How will this ecosystem ensure proper good governance and integrity are in place? What are the checks and balances, oversight, and monitoring mechanisms on DNB’s key performance indicators (KPIs), financial, legal, and technical matters? The appointment of the Board of Directors does little (if nothing) as far independent external oversight goes.”

Also, TM (Telekom Malaysia) had inked an RM2 billion deal to provide fibre leasing service to DNB. The government’s investment holding arm, Khazanah Nasional Berhad, also has a majority stake in TM.

MCMC is an agency under the Ministry of Communications and Multimedia, thus representing the government and not a “neutral” entity under the whole “government-led” DNB model.

- Another fundamental problem with DNB is in its simplistic thinking by analogy that 5G is already a universal “utility” in our country, like electricity or water, and by just “supplying” it, it will be readily and universally taken. Furthermore, its plan to force the MNOs to take on capacities would do very little when they cannot find the demand to fulfil those, especially in rural areas. A sluggish 5G demand (which is undoubtedly expected given Malaysia’s current weak digital ecosystem fundamentals) inadequate to cover minimum coverage capacity will not only negatively impact MNOs’ cashflows but also directly DNB’s bravados “securitised” cashflows and therefore become the taxpayer’s liability very quickly. Note DNB never provided any sort of demand analysis to substantiate its claims.

- Being overly obsessed with the urgency to push 5G into rural areas, can DNB pinpoint anywhere from the National 5G Task Force Report that 5G would be critical for rural coverage? How does, for example, entertainment and edge computing etc., based on enhanced mobile broadband (eMBB), massive machine-type communications (mMTC) and ultra-reliable low latency communications (URLLC) feature for rural users? Granted that the Internet of Things and, by inclusion, edge computing in supplementing Narrowband IoT for smart or digital farming/agriculture is critical, but this can still be perfectly run on 4G LTE lines which are, in fact, more suitable given the wide coverage area of the farm. In contrast, 5G is high frequency (millimetre waves), but low-band travels very short distances.

Although DNB has been vehemently opposing the involuntary comparison with 1MDB, we do see a very common pattern here—an entity with a very compromised and weak governance structure that does nothing, owns nothing but already have been spending money full speed securitising it with the future cash flows that we are very likely to never see.

Dr Rais Hussin is the President and Chief Executive Officer of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.