Published in Astro Awani, Malaysia News Today, The Star, Malay Mail & CodeBlue, image by Astro Awani.

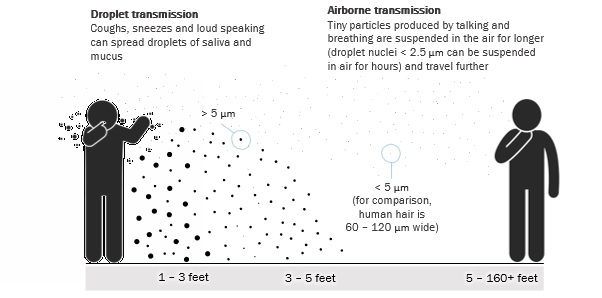

The scientific evidence accumulated for more than a year of the COVID-19 pandemic now more conclusively points towards the predominant long-range (> 5 feet) airborne nature of its transmission (Figure). To date, this important feature of the infection spread received only cursory attention from authorities and policymakers worldwide and more so by the general public. Therefore, our existing pandemic management measures focused solely on droplets and fomites transmission might be although extensive yet suboptimal effort.

Figure: Difference between droplet and airborne transmission

On April 15 2021, one of the most reputable scientific medical journals, The Lancet, has published the article titled “Ten scientific reasons in support of the airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2”. At about the same date, two other oldest top medical journals—The British Medical Journal (BMJ) and Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) have published articles written in a similar vein.

The following is the simplified summary of scientific reasons or facts listed by Professor Greenhalgh and her colleagues in The Lancet article, which strongly point towards the important (if not even predominant) role of airborne nature of COVID-19 transmission backed by accumulated scientific evidence.

The first such factor is the presence of super spreaders and super spreading events—where one infected individual becomes responsible for infecting a large proportion of those present in the same premise and not necessary within 5 feet from the infected. Only the predominant airborne nature of transmission could adequately explain the frequency of such situations in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, in a New Zealand study by Eichler and team, the researchers, while methodologically combining genomic sequence analysis and epidemiologic investigation, have proven the possibility of airborne transmission between people in adjacent quarantine hotel rooms who were never in direct contact with each other.

Third, according to the latest estimates, asymptomatic individuals are responsible for transmitting close to 60 per cent of all infections. Asymptomatic individuals are not sneezing or coughing much. Therefore, it is pretty difficult to explain such a distribution of infections unless we consider the role of airborne transmission. The smallest particles (droplet nuclei < 5 μm) laden with the viable virus and capable of travelling long distances in the air are found to be emitted even while low voice talking or just breathing.

Fourth, it is well established that the risk of COVID-19 transmission is significantly lower outdoors than indoors and in well-ventilated versus poorly ventilated indoor settings consistent with its airborne transmission.

Fifth, the COVID-19 spreads were reported in hospital environments with protective measures explicitly designed to address large droplets concern but not the possibility of airborne transmission.

Six, scientist detected viable COVID-19 virus in the air samples in laboratory conditions for up to 3 hours. However, detecting airborne virus outside of the laboratory settings is challenging due to mechanical damage during sampling. Authors also stress that other infections such as measles and tuberculosis, whose primary airborne route of transmission is undeniable by now, “have never been cultivated from room air”.

Seven, in Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden, scientists detected SARS-CoV-2 N and E genes inside the ventilation HEPA filters located far outside the range to be explained by large droplets transmission. In the said Sweden study, the researchers could extract only genetic material rather than viable virus due to sampling challenges described earlier.

Eight, another scientific experiment supporting airborne mode of SARS-CoV-2 transmission has been conducted in the Netherlands. Jasmin Kutter and her colleagues have demonstrated transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to two of four indirect recipient ferrets and SARS-CoV to all four while eliminating the possibility of direct transmission between animals’ enclosures.

Ninth, to the best of Professor Greenhalgh and her other reputable colleagues’ knowledge, no study so far “has provided strong or consistent evidence to refute the hypothesis of airborne SARS-CoV-2 transmission” while empirical evidence of otherwise is piling up continuously.

Tenth, the authors demonstrate inconclusiveness of arguments that to date have been put forward in favour of predominant close-contact (large droplets and fomites) mode of COVID-19 transmission. A higher risk of close-contact infection does not prove that the COVID-19 virus predominantly travels in droplets and does not contradict the hypothesis about its airborne transmission.

How convincing does all of this sound? It must be compelling enough that even World Health Organisation (WHO), on April 30, 2021, have updated the English version of its Q&A section with regards to COVID-19 spread between people by adding a para that underscores the possibility of long-range virus transmission in poorly ventilated and/or crowded indoor settings. Note that previously WHO and the Centre for Disease Control and prevention, although not outright denied the possibility of large-distance airborne nature of COVID-19 transmission, but solely emphasized the close-contact or short-range modes of transmission (large droplets and fomites).

The other two articles in BMJ and JAMA journals echo the proposition about SARS-CoV-2 likely having a predominant airborne transmission route. They also discuss the implications of this scientific finding for the effective non-pharmaceutical intervention.

Wearing masks, physical distancing, limiting indoor occupancy and crowded outdoor activities remain relevant measures to curb the infection either from direct contact with surfaces or droplets or from inhaling droplet nuclei. However, when we consider accumulated scientific evidence about COVID-19 airborne transmission, few concerns immediately arise about the sufficiency of the existing efforts.

First, the engineering control of indoor air quality—ventilation and filtration—in our work environment, educational institutions, shopping malls, other recreational public spaces, and even our homes become essential. It is the pertinent question what are the current conditions of our ventilation and filtration systems in all these spaces nationwide? Except for hospitals, they might be set for bare minimums and not designed for effective infection control.

The airborne nature of COVID-19 transmission would call for a thorough revision and upgrade of ventilation and filtration standards and systems nationwide. Public spaces deserve immediate attention.

As an immediate urgent solution increasing the humidity level in public spaces would significantly reduce travel distance of droplet nuclei laden with the virus. Additionally, IoT devices measuring CO2 concentration can be placed strategically to alert about presence of areas with dangerous levels and thus calling for sanitation. In public spaces, it is also possible to think of gaseous disinfectant (similar to the one sprayed before airline takeoff) released periodically throughout the day.

In the long run, authorities must make ventilation and filtration standards, required to combat airborne infections effectively, part of development standards. Allen and Ibrahim discuss at length the required targets for ventilation and filtration in various settings grounded in the basics of exposure science in the aforementioned JAMA article published on April 16, 2021.

Also, reducing taxes for anyone who is in manufacturing, installing, and maintaining high-efficiency ventilation and filtration systems will increase general public access to it nationwide.

The revision and upgrading of ventilation and air conditioning systems might seem a daunting task associated with many fixed costs. However, the tremendous savings and other benefits that can be realized from improved public health and reduced sick leaves for other respiratory viruses nationwide might far outweigh the costs. Additionally, the use of “smart” systems tracing the occupancy or CO2 concentration may significantly reduce the cost of operating such systems.

Such an indoor air control system overhaul nationwide would also increase our resilience and reduce costs associated with possible future pandemics and air quality-related disasters. But it is also crucially important now when we do not know how long more we will have to combat COVID-19 and its possible variants.

The second big concern is the quality of masks used—high filtration efficiency and a tight fit are simply crucial for adequate protection against inhaling aerosols. The airborne nature of COVID-19 transmission also requires tailoring intervention strategies and tightening SOPs for locations where masks are not worn all of the time, for example, in restaurants. For waiters wearing high-efficiency masks and for patrons wearing masks at all times only except eating is probably mandatory.

The accumulated empirical evidence of airborne COVID-19 transmission discussed here should not only make governments and health leaders heed the science and re-focus their efforts but also make the general public more cautious and vigilant in compliance with the SOPs. Don’t let your guard down. This virus, SARS-CoV-2, might be more subtle and ubiquitous than we think it is.

Dr Rais Hussin and Dr Margarita Peredaryenko are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.