Published by AsiaNewsToday, CodeBlue & AstroAwani, image by AstroAwani.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines mental health as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community … Mental health is more than the absence of mental disorders” (“Mental health: Strengthening our response”, WHO, June 17, 2022).

Mental health encompasses our psychological, emotional, and social health.

In 2015, it’s reported that 29.2% of individuals aged 16 and above had mental health problems in Malaysia (“National Strategic Plan for Mental Health 2020-2025”, Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2020).

Of this, East Malaysia had the highest prevalence rate of a population meeting the criteria of mental disorder at 43%, followed closely by Kuala Lumpur at 40% (“Mental disorders in Malaysia: An increase in lifetime prevalence”, Raaj et al., British Journal of Psychiatry International, Vol. 18, Issue 4, 2021).

As Malaysia develops from a middle- to high-income country, levels of stress have also been increasing.

Mental health in the workplace

Increasing demands of workload, competition and globalisation have been associated with increasing mental health conditions (“Struggle over employees’ psychological well-being. The politicisation and de-politicisation of the debate on employee mental health in the Finnish insurance sector”, Koukkanen et al., Management and Organizational History, Vol. 15, Issue 3, 2020).

Only last year, it’s reported that 51% of our workforce have had work-related stress (“Mental health protection for the workforce”, The Star, August 16, 2022).

However, it’s estimated that only 20% of Malaysians with mental health issues get the treatment they need (“Workplace mental health: The business costs”, Relate Mental Health Malaysia, 2020).

High prevalence of mental disorders translates into increased costs to organisations and severe strains on the economy. Lower productivity and increased absenteeism are the leading causes behind these financial losses (“Exploring mental illness in the workplace: The role of HR professionals and processes”, Hennekam et al., The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 32, Issue 15, 2021).

Poor mental health is seven times more likely to make an employee unproductive.

According to an Australian study, psychological distress can decrease productivity by 26%. In the UK, the statistic was around 40%. Depression alone accounts for over 15% of loss in productivity.

WHO estimates that poor workplace mental health costs the global economy USD1 trillion annually. In Malaysia, poor mental health in the workplace costs the country’s economy around RM14.46 billion or 1% of the GDP.

Given such drastic financial losses, it doesn’t make sense to not invest in the mental health of our workforce.

Of course, there’re many things an organisation can do to boost their employee’s mental health – and thereby their productivity – such as providing flexible working hours, respecting non-office hours, and promoting healthy work culture.

While such measures are useful in improving mental health conditions, therapy is also an indisputably critical aspect of improving mental health.

Lack of laws related to mental health in the workplace

The Malaysian Mental Health Act (2001) and the Mental Health Regulation (2010) make no provision regarding mental health in the workplace (“Mental Health Issues at Workplace: An Overview of Law and Policy in Malaysia and United Kingdom”, International Journal of Law, Government and Communication, Vol. 6, Issue 22, 2021).

The Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) 1994 posits that employers are liable “to ensure, so far as is practicable, the safety, health and welfare at work of all his employees”. However, the Act primarily focuses on the physical safety of the employees and has no explicit provisions regarding an employer’s duty towards mental health, especially depression, anxiety, and stress.

Scarcity of employee mental health insurance plans

Most employers provide health insurance as an incentive and in line with good practice. However, currently there’re no laws in Malaysia that require employers to provide health insurance to employees, let alone mental health insurance.

There’s a severe lack of employee mental health coverage plans offered by insurance companies. This is accompanied by poor awareness amongst employers about the possibility of mental health coverage.

In August 2022, AIA was the first to launch a mental health employee insurance programme in Malaysia in collaboration with ThoughtFull, a digital mental health organisation. The insurance plan offers unlimited daily digital 1-on-1 therapy with professionals, 24/7 wellness hotline and mental wellness programmes. It includes coverage for employee consultation, medication and treatment as provided by a psychiatrist (“Mental Health Protection for the Workforce”, AIA, August 16, 2022).

The crux of the issue for employers in providing mental health insurance to their employers lies in one simple question – is it worth it?

Inarguable importance of mental well-being in the workplace

Mental well-being is linked to increased creativity, motivation, curiosity, cognitive flexibility, broader array of ideas and problem solving, improved ability to consider numerous options and increased resilience.

All these skills are instrumental for the growth of a company.

Mental health therapy improves job performance

In 2010, a study found that access to therapy can decrease employee sick days by half. Less sick days translate into more work done for employers. Furthermore, being happy increases an employee’s engagement with their work and employee productivity by 12%. Google, by providing therapy, reported a 37% increase in employee satisfaction and productivity.

A study with 197 employees from two Fortune 100 companies receiving counselling through an Employee Assisted Program (EAP) provider suggested that just 90 days after starting the counselling, employees showed significant decreases in absenteeism, presenteeism, workplace distress and increase in life satisfaction (“Evaluating the Workplace Effects of EAP Counseling”, Sharar et al., Journal of Health & Productivity, Vol. 6, Issue 2, 2012).

Mental health therapy is cost-efficient

Given that most organisations are private and for-profit, it seems counterintuitive for employees to invest in mental health which is seemingly intangible and difficult-to-measure. However, research suggests that investing in employee therapy both saves and make money for organisations (“Is Therapy an Effective Provision for your Employees”, Spectrum Mental Health, April 19, 2018).

Research suggests that it’s extremely costly for employers to not invest in employee mental health. In the US, depression costs employers USD17 per employee annually, a stark difference from the next highest health cost – diabetes costing less than USD2 (“What do employers need to know about parity?”, American Psychological Association (APA), May 5, 2021).

Additionally, an increase in mental health issues has shown to increase employer expenditure on physical health problems. WHO estimates a USD4 return through productivity and health for every USD1 spent on mental wellbeing.

The following presents a cost-benefit analysis done by Relate Mental Health Malaysia on investing in workplace mental health insurance in Malaysia:

Productivity is calculated using three factors: (1) Absenteeism, (2) Presenteeism, and (3) Staff Turnover.

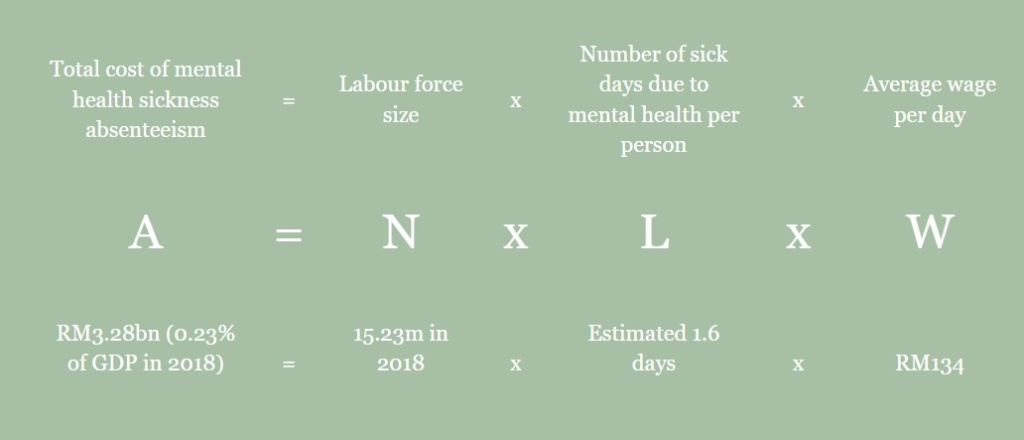

(1) Absenteeism – employees missing a whole or part of the day of work due to mental health illness (Figure 1).

Figure 1

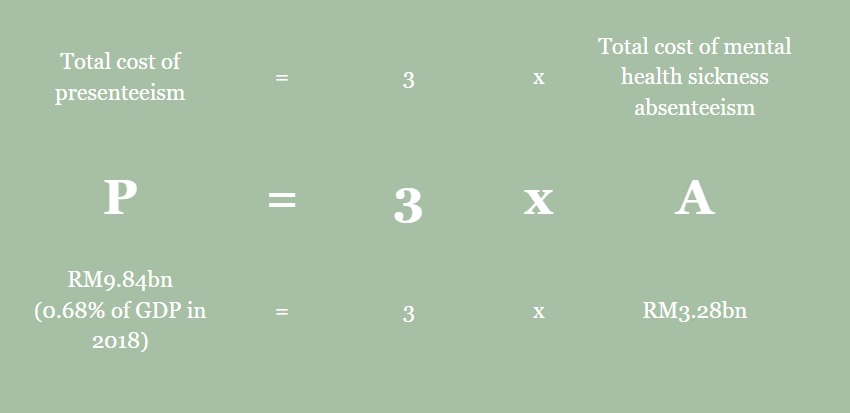

(2) Presenteeism – employees going to work despite being ill. The cost of mental health presenteeism in Malaysia has been estimated to be around three times the cost of mental health absenteeism (Figure 2).

Figure 2

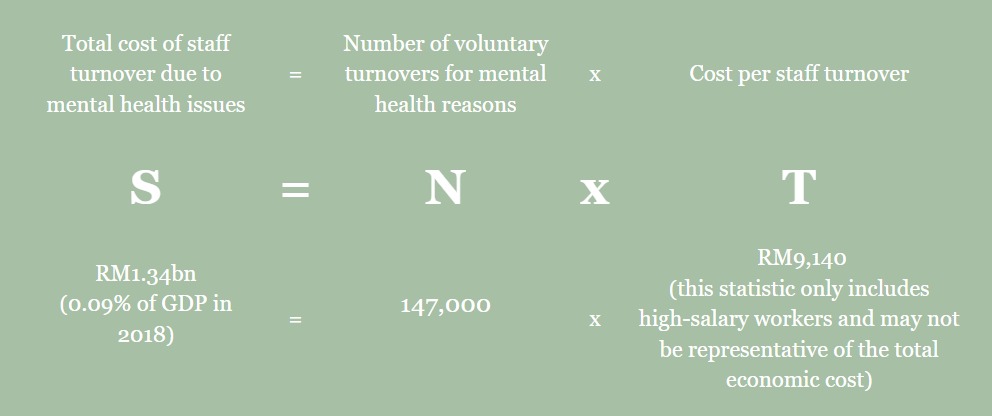

(3) Staff Turnover – number of employees leaving a company (Figure 3).

Figure 3

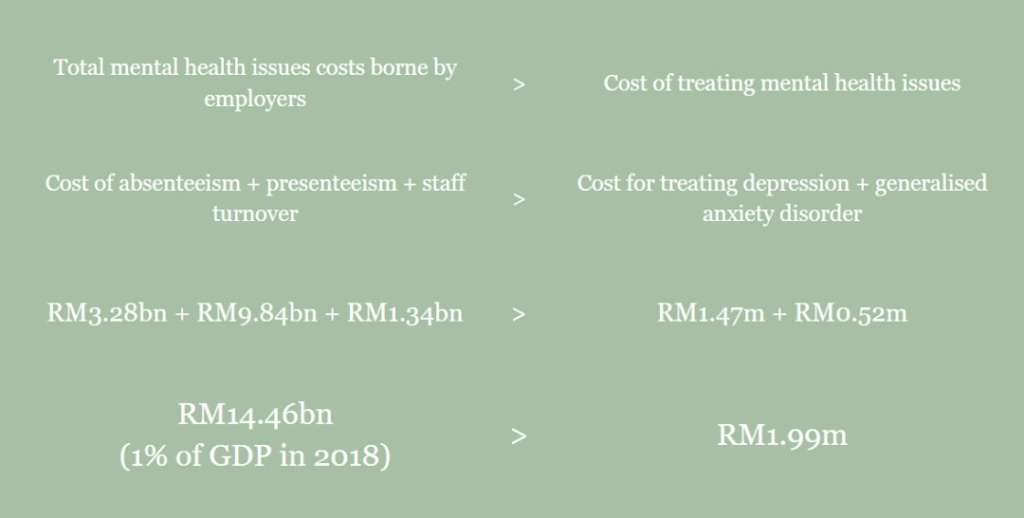

Total workplace mental health cost to employers in 2018 vs estimated costs of treating mental health (Figure 4):

Figure 4

As can be seen, the annual estimated cost for treating depression and anxiety in Malaysia is markedly lower than the annual cost of lost productivity due to mental health issues.

The RM14.46 billion cost has no doubt increased over the past 4 years especially exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This figure doesn’t even include the cost of treating physical health problems caused or exacerbated by mental health issues. The RM14.46 billion costs due to mental health issues at the workplace dwarfs the mere RM337 million allocated to mental health issues in 2022 budget (“What We Know So Far: A Breakdown of Budget 2021’s Allocation for Mental Health”, Relate Malaysia, November 19, 2020).

Employers can’t avoid hiring employees with mental health issues anymore

While companies may be motivated to only hire mentally “healthy” individuals, such a strategy doesn’t take into account the possibility of employees developing a mental health condition during employment.

An employee without any history of mental health issues is 7% likely to develop such a condition and 13% if they are stressed.

Given that 51% of workers in Malaysia report high occupational stress, companies wanting to avoid employing individuals with mental health issues isn’t possible. Hence instead of avoiding this, employers should embrace encouraging and supporting mental health.

While 63% of employers recognise that employee health and well-being impacts company success, only 13% of employers are aware of potential well-being interventions. This suggests a severe disconnect between employer beliefs and the subsequent implementation of appropriate budgeting and processes safeguarding employee mental health.

Addressing mental health issues benefit employers in other crucial ways as well such as boosting their reputation, promoting a healthier work culture, and greater employee commitment and loyalty.

Hence, EMIR Research recommends:

- Including specific provisions regarding mental health in OSHA (1994);

- Workplaces to hold mandatory mental health awareness seminars once a year – which should be claimable via the Human Resource Development Fund (HRDF);

- The Ministry of Health (MOH) and Ministry of Finance (MOF) to work closely with the Malaysian Mental Health Association, Malaysian Society of Clinical Psychologists and insurance companies to introduce more employee mental health insurance schemes especially focusing on depression, anxiety, and stress;

Insurance schemes should also include first line of treatment such as initial consultations and psychotherapy, instead of solely including psychiatry and medication which are mainly used for more extreme cases;

- Ensuring complete confidentiality regarding the content of therapy from the employer and the insurer;

- A mental health necessity “criterion” to prevent/pre-empt the possibility of insurers using their own pre-computed actuarial risk analysis calculations that might result in unfairly denying workers mental health treatment.

Reference can be made to the two statements/recommendations issued by the APA, namely that –

“Requirements related to prior authorization of treatment and medical necessity determinations must also be comparable and no more stringently applied to mental health coverage than physical health coverage”.

And “[c]o-payments, coinsurance, deductibles, and out-of-pocket costs for mental health benefits cannot be higher for mental health services than the co-payments for physical health benefits”.

In conclusion, EMIR Research strongly urges the government and insurance companies to work together under a public-private partnership (PPP) and develop comprehensive mental health insurance plans to improve both the organisational and economic outcomes, among others.

Jason Loh and Juhi Todi are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.